Robert Coover's Metaphorical Toy Box:

Aleatory – No, Relentlessly Ludic – Yes

ELISABETH LY BELL

While Coover aficionados are impatiently awaiting The Brunist Day of Wrath, the massive, 392,000-word sequel1 to his 1966 debut novel The Origin of the Brunists, that impasse of almost half a century might be well spent by looking back at one of Coover's smaller texts, the 90-page novella Stepmother (2004), in which he masterfully investigates, continues and then reinvents the Grimm Brothers' fairy tales, all Coover-style. And that means his dense tale contains less fairy but more sex, not always of the pleasant kind.

Fairy tales, a specific genre of the folktale, arose from a communal, oral form of storytelling and have been used as such by Coover:

As I began writing I found certain commonly used forms extremely restrictive; they seemed like lies. It was fun to make up those lies and make money at it, and when I was young I thought that's what it was to be a writer. As I became more reflective about my own processes of thinking and writing, the whole question of form and structure became more problematic and I began experimenting—on my own and on the basis of things I had read, including fairy tales. I became more intrigued by these other forms and that writing of the novel tradition that has been perceived as out of step, such as Tristan Shandy.2

Although he almost exclusively raids the Grimm Brothers' canonical Märchen, he also wrote three treatments drawn from other sources. In Aesop's Forest (1986), matters are not quite as fabulous as in the Greek fabulist Aisopos' stories, who most likely was not a historical figure but instead a fiction himself. Coover here reformulates the didactic-moralistic aspect as well as the allegorical style of the fable snarkily and with relish. Next, in 1991, he took another detour south and created the continuation to and the true end for a famous Italian fairy tale in the extended narrative of Pinocchio in Venice. In many ways the highlight and summation of Coover's expert manipulation of pre-existing texts (Collodi, Thomas Mann, Disney), the novel "ends with a pivotal transformation—perhaps the most overtly symbolic transformation in all of the literature influenced by the fairy tale—and this is certainly one of the dominant themes in Coover's choice of intertexts."3 Lastly, Coover's rendition of Charles Perrault's Bluebeard, "The Last One" (in A Child Again, 2005), is narrated in first-person from the wife-killer's point of view, and features not only a switch in narrator, but also a role reversal at the end, and a mischievous question from the childbride—almost like the last question in Charlotte Perkins Gilman's 1892 short story "The Yellow Wallpaper": "Now why should that man have fainted?" A paranoid Bluebeard is at the forbidden door, "hacking wildly at it . . . . And, as I break through at last, she appears behind me. Oh my, she says. Whatever are you doing?" (251).

Returning to the Grimm Brothers, the publications of Briar Rose (1996)—his non-hierarchical, multi-narrative version of Sleeping Beauty—and of Stepmother exemplify the road Coover has taken since his first treatment of fairy tales in 1969. When dealing with that particular traditional form of storytelling and its influence, he does not draw from modern sugarcoated versions—or, even worse, from the Disneyfied ones—but instead goes back to their ur-forms. In general, Coover exploits the complete stock of European and American fairy tales, fables, and legends for his fictional transformations, as for example in "The Door," when he mixes up three classic, independent folktales from the Old World with one from the New World into one multi-fairy tale, which—apart from all the other and much more important intensions of that introductory story of Pricksongs & Descants—renders highly amusing relationships among family members. Or the linguistic excesses in "The Dead Queen" (1973), which tells the Snow White story from the perspective of the inebriated Prince, with a frigid Snow White and sex-obsessed dwarves, who, in an obscene scene, beat him to the defloration. This Prince is convinced that the Old Queen "poisoned us all with pattern" (306), thus articulating his "dissatisfaction with his own mimetic imagination. . . . [S]exuality and its politically framed power games have played a central role in Coover's self-consciously interruptive and hypertextual re-awakening of dormant metaphors in fairy tales."4 Or in "The Gingerbread House" (in P&D), his deconstruction and expansion of Hansel and Gretel, which in the Grimm version has both women connected to food: the Stepmother worrying about it and the witch with her edible house and her plan to eat the children. In Coover's rendition, the children's phase of oral fixation—the witch's gingerbread house is described in erotic terms—leads to the initiation into the joys of sexuality. Further going beyond the Grimm original, these children also face the presence and inevitability of death, symbolized in the witch. Different from "The Door," the boy and the girl are not yet ready to take the step into adulthood and remain doubtful and fearful at the door. But the last of the "The Gingerbread House's" forty-two fragments ends with the kids ecstatically amusing themselves at the edible house, the entrance in view: "Oh, what a thing is that door! Shining like a ruby, like hard cherry candy, and pulsing softly, radiantly. Yes, marvelous! delicious! insuperable! but beyond: what is that sound of black rags flapping?" (75) – Eros and Thanatos.

Coover uses Eros and Thanatos less in a Freudian, dualistic sense but instead his work shows the relation between sexual fantasies and death, and sex is always also one way to counter death, and a symbol for union and continuity. Asked whether he is using eroticism as a technical device, he replied:

I hope not. What kind of lover would I be then? As a widely shared communicative experience, of course, sex can be used fictionally in a variety of ways as an exploratory mechanism: any concern can be deflected into it, ideas, as it were, fleshed out. But at heart I believe, along with Hesiod and Ovid, that Eros powers the universe and you ignore it at your own peril and at the peril of the truth of the piece you are writing. It is not necessarily something humane or rational or even attractive, but it is a force not to be denied. My policy is skeptical surrender. 5

Coover's fairy tales can be discussed applying Bruno Bettelheim's psychoanalytical approach or the opposing, historicizing view of culture critic and fairy-tale expert Marina Warner. Even though both authors correctly and sharply distinguish between myth and fairy tale, the functional and structural common characteristics of both communal forms of storytelling offer a more productive assessment: both forms provide role models and a sense of social and cultural identity; both have underlying archetypal patterns and use symbolic images in mediating content; finally, "both the oral and literary forms of the fairy tale are grounded in history: they emanate from specific struggles to humanize bestial and barbaric forces, which have terrorized our minds and communities in concrete ways, threatening to destroy free will and human compassion. The fairy tale sets out to conquer this concrete terror through metaphors."6

The latter are of great interest to Coover in all his writing—both in his fictions and his essays—namely whether the metaphors through which we perceive the world still carry meaning or are simply dead metaphors, be they in myths or in fairy tales. "The large metaphors that sustain novels contain the world: religion, sex, family, history, politics." 7 Coover's particular attention goes to the intersection, the tipping point at which the content of an image becomes so hazy that the transfer is no longer ensured. It's at that juncture Coover sees ironies and paradoxa, which he picks up, transforms and fills the blanks with "fresh" meaning. In an interview, he stated his undertaking this way:

When you deal with any kind of mythic experiences of non-literal explanation and exploration of life, there's no way to cope with them literally. You can't pin them down; they don't allow themselves to be pinned down. And the only way to cope with them is to deal with them in their own language, the language they deal with themselves. So I like to use the original mythical materials and deal with them on their home ground, go right there to where it's happening in the story, and then make certain alterations in it, and let the story happen in a slightly different way. The immediate effect is to undogmatize it so that at least minimally you can think of the story in terms of possibility rather than as something finite and complete. This is as much true of Red Ridinghood as it is of Jesus. 8

The ubiquity of the evil Stepmother "has over time emerged as the marquee fairy-tale villain," 9 most famously so in Snow White, Hansel and Gretel, and Cinderella, but long before the wicked Stepmother motif appears in myths all over the world. In fairy tales, maternal malevolence is usually directed toward stepdaughters, but such filicidal mothers sometimes also find victims in stepsons. Frequently, the animosity between the Stepmother and her stepchild is amplified when the daughter receives help from the deceased mother. Historically, though, real conflicts can be traced to women dying in childbirth, or to attempts at securing an inheritance for biological children. In-depth studies reveal that the Stepmother character in fairy tales has undergone quite a change. In the original Grimm fairy tales of 1812, most of them are the biological mothers, not Stepmothers. What caused the Grimm Brothers to make this switch, to sanitize their tales? The psychoanalytical view of splitting mother images into two components is applied in Maria Tatar's The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Tales (2002), which examines the dual identity of female villains and their stand-ins: cooks, witches, evil servants, female ogres, or hostile mothers-in-law.

Coover's Stepmother presents—at least up to now—the climax of his playful assaults on classic fairy tales, since this novella demonstrates that Coover is not only familiar with the 200 Grimm tales and the ten Children's Legends in the appendix of Kinder- und Hausmärchen (Children and Household Tales), but that he also goes back to the first (hardly known) edition of 1812, which still features horrible cruelties, incest, or pregnancies before marriage. In consecutive steps, over six editions after the first one, culminating in the famous and final edition of 1857, the Grimms sanitized such horrors and rendered their tales more child-appropriate. No such softening-up with Coover.

In 2005, he talked about the beginnings of his writing, stating that "Along the way I've been creating these little fictions dealing with stories from our infancy," and goes on to say that together with "religion and patriotic legends . . . we get a lot of children's stories that leave a bit of residue, maybe we forget the story but we are stuck with something of it, some of it is OK. When I go back and examine these old texts, or old ideas, or old stories, sometimes I find things I like and I bring them out. Most of the times I find problems and confront them." 10 The latter definitely is the case here: Stepmother, without a personal pronoun, indicates in the title already that the text will not be about a particular Stepmother but rather will deal with a type, and turns out to be a treasure chest for fairy-tale detectives. Who, when reading about Stepmothers and their daughters, would think about Hypatia of Alexandria (370-415), the Egyptian Neo-Platonist philosopher who was the first notable woman in mathematics? Out of political envy, this highly educated teacher was accused of sorcery and practicing magic, upon which a fanatical mob of Christian monks seized her, completely stripped and killed her with sharp tiles. After the mutilation, her mangled body was dragged through the streets and her remains were burnt. A similar fate awaits Coover's stepdaughter.

At first glance, it is simply the story of a Stepmother who tries to rescue her daughter from execution with all the magic available to a witch. In the text to follow, Coover inimitably mixes the standard repertoire of fairy-tale characters with plotlines of at least thirty-five lesser-known fairy tales. 11 In the magic forest the rebellious Stepmother's adversary is Reaper, personifying the status quo, whose biggest fear is "meaninglessness" (12) and who "does not disturb the way things are and is angered by those who do" (13). Stepmother knows all too well about "the Reaper's enigmatic designs" (51). "I can see the Reaper's hand in this. He feeds on pattern and pattern has caught my daughter out. . . . And there are other plots afoot here. . . . My daughter might be only a minor player in the larger drama still unfolding" (50). The third major character is Old Soldier, the intermediary between Stepmother and Reaper, while a final actor on stage is Reaper's Woods, quite literally the setting, but at the same time telling the magic-forest story:

It has no owner and it and its denizens were here long before he [the Reaper] came to it, but he has put his stamp on it with his meditative prowlings and has opened it to public view, and in the popular fancy, the forest is his by default. . . . Nor are frogs the only bewitched. Indeed, just who or what anything or anyone here is—animals, trees and flowers, people, insects, birds, even aromas and clouds of dust—is always open to question, so infested with enchanted beings is the forest. (8) Justice here is fierce and final. Only a master wizard can reverse it, but rarely does so, for character is character and subject to its proper punishment; tampering with endings can disturb the forest's delicate balance. (11)

At second glance, Stepmother is a complex treatise on story-telling per se, on the writing of stories, on story, idea, and endings. Already in the first paragraph Stepmother talks about her grief over lost daughters, stating: "and thus we keep the cycle going, rolling through this timeless time" even when her "spells collapse for a fault in grammar" (2). The issue in the novella's fourteen, unnumbered sections is control over Story and Idea, its ur-forms and applications, and who has the power to determine or change that form, to break free in a big grand from established ones and uncover the darker, bawdy and/or salacious sides. Magic here stems less from the Stepmother-witch—her tricks more often than not fail to work any more anyway—but instead emanates from Coover's wonderfully precise and at the same time jocular language, which balances between arch-satire and fantasy, and, simultaneously breaks open the fairy-tale hierarchy from within.

So there are different kinds of magic at work here: the author's use of language, and the magical realm of imagination where frogs turn into princes, wishes come true, death can be reversed, dead mothers help daughters from beyond the grave, animals and objects speak, a lowly tailor marries the princess. Marina Warner, the foremost theorist of myth, fairy tales, and folktales, explores the enduring appeal and power of those stories in Stranger Magic (2012) and finds the creative activity of the imagination being stimulated by the fairy tales' magic. Tracing their increasing popularity back to the Enlightenment, Warner explains the magic of enchantments, which she calls "charmed states":

Magic is not simply a matter of the occult or the esoteric, of astrology, Wicca and Satanism; it follows processes inherent to human consciousness and connected to constructive and imaginative thought. The faculties of imagination—dream, projection, fantasy—are bound up with the faculties of reasoning and essential to making the leap beyond the known into the unknown. At one pole (myth), magic is associated with poetic truth, at another (the history of science) with inquiry and speculation. It was bound up with understanding physical forces in nature and led to technical ingenuity and discoveries. Magical thinking structures the processes of imagination, and imagining something can and sometimes must precede the fact or the act; it has shaped many features of Western civilization. But its influence has been constantly disavowed since the Enlightenment and its action and effects consequently misunderstood.12

As a traditional fairy-tale stock character, the Stepmother represents power within a fairy tale, easily determined by her having control over consumption goods and commodities. Stories with Stepmothers usually begin with a painful loss, the death of a birth mother. Evil-minded, bad Stepmothers typically act out of poverty or envy (as in Hansel and Gretel or Cinderella), while the truly evil Stepmothers seek to kill their stepdaughters (Snow White). How different in Coover's Stepmother, where she is a caring, loving mother, albeit with rather pragmatic, unsentimental traits. She is a fighter, not only for her daughters but for the power of fantasy, because she is convinced, "Still, hopeless though it may be, you have to keep laboring against the way things are" (49) and at the same time envisions how things should proceed: "I'm beginning to grasp something of the untold tale" (51). Yes, Stepmothers can be witches but Coover's variant is a tireless savior of daughters and of Story. Her appearance and championing pertain to the forces which have become too powerful, have become a danger because they attempt to suppress the visionary. And that's why Stepmother tries to alter the course of her story and of Story, always keeping in mind that there is a possibility for escape, an exit, or a way out other than the designated, forever predetermined one. "Using fairy tale characters as the depository of their own tradition allows for the suggestion of alternatives beyond the limits of the standard dénouement, while the idea of the fairy tale as historically sanctioned lie is itself complicated by an undercutting of the archetypal characterization." 13

In the polyvocal Stepmother, only the title character speaks in the first person but the other narrative strands infiltrate the consciousness of Reaper, Old Soldier, and the Wood (and the daughter). The Reaper, "gently mannered son of the city" (12), keeper of the tradition and would-be womanizer, envies Old Soldier: "Freedom: that's what Old Soldier celebrates, and what the Reaper in his earnestness sometimes longs for" (16). Yet even more, he begrudges Old Soldier his ability to tell a good tale. Old Soldier, on the other hand, is well aware of that envy and clearly assesses his preferred listener, rendered in his distinctive diction: "Is the Reaper a saint? Could be, the moralistic old buzzard, surrounded by that hardass phantom gang of his, so intent, the lot of them, on bludgeoning the world with piety" (36). Piousness and reverence simply are not part of Old Soldier's vocabulary, and he knows that the more smutty, lewd and seamy his stories are, the more Reaper will appreciate them. "He even takes notes. Probably fancies himself a storyteller but lacks invention of his own" (37). What really interests Reaper are the "in-between bits, as you might say, the wet and hairy stuff of story" (40). Other inhabitants of the Wood monitor the Reaper as well. In the middle of section thirteen, the Grimm Brothers' Fitcher's Fowl is mixed up with other fairy-tale set pieces, only to then modify that particular story with "This at least is the Reaper's version of history, a favorite of his. Others see it in another light or emphasize different details, for it happened long ago and much has been forgotten or transformed by time's own subtle poetic gestures" (80).

But Reaper is also the authority figure in the Wood and over Story. In the novella's second section, he is described as "a tireless seeker, but what is he seeking? The revelation of some kind of primeval and holy truth, he would say, the telltale echo of ancestral reminiscences. The urmythos" (14). Later on, Coover returns to this topic, when Reaper meets a passing minstrel disguised as the Devil and thinks, "The urmythos is omnipresent, but it is not something fixed; one can shape it. And so, as one can, one must" (31). And that's exactly what he does at the end of the novella, when he sees through Stepmother's stalling maneuver and replies to her pleading for a typical ending: "Not all legends are true" (89).

Serious, strict Reaper's antitype is Old Soldier, a hilarious, jovial, dirty old man and in many ways typical Cooverian, linguistically presented in both his "Good Ol' Boy" idiom and reminiscent of Beckett: "This really happened. Probably" (76). He is the prototypical storyteller—"Always time for a good story" (19)—as well as the preserver of stories, without ever rendering judgment on the stories, his motto being: "All in how you tell it, he reminded the terrified captain before his quartering, giving him his cider jug to suck" (72). Old Soldier is down-to-earth, frequently drunk, a gamester, who in his "long happy life" (35) has taken on many roles, once even as the pope. Playing that part, he particularly enjoyed confessions, "but otherwise it was shitwork" and therefore he hands the job over to the Devil, glad "to find someone to take his place, a fellow more suited to the game with eyes as red as his cardinal's biretta and a pair of horns under it." Next, he decides "keeping his distance from saints of either sex, all those self-righteous sparrow-asses with their otherworldly fevers" (35). He has been around in the world, has been to heaven and hell,

has had the Grand Tour, above and below" . . . But worst of all in that other world where, as part of the deal, all such have ended: no more stories. Which is what the Old Soldier lives for, bugger the rest. Story's often saved his life, story is his life, and he sometimes gets the feeling that, though he has committed crimes far worse than those for which Stepmother's daughter will be hacked up and killed, he'll be spared the gibbet, thanks to his stories and his retelling of them. An end to all that? Unimaginable. (36)

Almost unbelievable, too, is Coover's range of material: the whole novella is rampant with direct references but also with countless allusions to and fragments from fairy tales. In the opening chapter alone, The Frog King, some sacks of gold, Cinderella, Snow White's poisoned apple, a hateful and revengeful stepsister, and a magic horn bringing down walls Old Testament-style, are all intertwined to form a new plotline, all in one paragraph. In the second section, Stepmother has taken refuge at Reaper's Woods with her rescued daughter, where countless other refugees are hiding. The following listing demonstrates Coover's play with fairy-tale elements: "The woods harbor witches, murderers, robbers, dwarves and giants, savage beasts, elfin angels, fortune-seeking boys and terrified girls, poor woodcutters, adventuresome tailors, lost minstrels, prophesizing birds and bewitched frogs" (8). But since this is an enchanted forest, one cannot always trust what one sees or believes to see. "Offended sparrows peck out eyes and hedgehogs strip and stab unloving ladies. It's true, there are also giftgiving toads and gnomes and ducks and even stars, and gold can be found in everything from feathers, fish, shoes, eggs and apples, dishware, straw and lilies to maiden mouths and donkey rectums, whence (from both, like twinned troves) golden cascades sometimes fall, but few survive the tests imposed by previous owners to acquire these riches" (10–11).

When Reaper tries to find and catch the escaped Stepmother, he encounters yet another balladeer, "singing a sad song about a maiden whose arms have been chopped off at the elbows for refusing to marry her own father" (29). Under Coover's treatment the Grimm Brothers' The Girl without Hands is maimed even worse than in the original – "her mutilations (which also included the chopping off of her breasts)" – and her story is fused with the fairy tale of Allerleirauh (All-Kinds-of-Fur), whose father eagerly wants to marry his daughter. Obviously, the Grimm heroine doesn't, but Coover extends his version to the actual incest since this young woman has a child, either from her father or her brother: "there's a certain ambiguity" (30). Since Reaper does not like that song and would rather hear a new, never-before-heard one, the minstrel offers him sixteen possibilities, but emphasizes, "All my songs are old songs, sir, but they will seem like new to hear me sing them.

Do you like songs about golden children or enchanted brothers or maidens who weep pearls? Faithful servants turned to stone. Poor tailors who become kings? A betrayed lover who is so sad she turns herself into a flower, hoping to be trampled, or a thumbsized boy swallowed by a cow? It has a funny chorus line. I also have one I think you'd like about four fellows who divide up the moon and take the pieces with them to their graves, awakening the dead with so much light. It's kind of a party song. Or perhaps your preferences run more to robber bridegrooms and castles of murder and hanged men with talking crows on their heads? . . . The maidens in the well! Sleeping beauties! The miller's apprentice and the cat-woman! (33–34)

Nevertheless, Reaper is still not satisfied with even that wide selection and finally demands a song "about how a peasant made a fool out of the Devil" (34), hinting at the Grimms' Brother Lustig, 14 a fairy tale playing a central role in Old Soldier's stories. Subsequently, Old Soldier tells his version of the meeting of Brother Lustig and Saint Peter, relating his wicked riff on the original. Indeed, the sections with Old Soldier as the main character offer the most widespread listings, innuendoes, and games with Grimm fairy tales, mostly not about the ones for children, all filtered through Old Soldier's coot-like humor: Little Brother and Little Sister, Brother Lustig, The Blue Light, The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was, Thumbling, Old Hildebrand, Iron John, The Singing Bone, The Drummer, The Devil's Sooty Brother, Frau Trude, and How Six Men Got On in the World.

A fourth perspective next to the voices of Stepmother, Reaper and Old Soldier is embodied by the enchanted forest. Once again Coover expands a core element of traditional fairy tales, which can be summed up with: "The deep forest where so much of the action takes place both stands for the human psyche and eludes such reduction." 15 In Stepmother, however, "Reaper's Woods, […] is said to reach to the very end of the earth where the sun eats wayward children and the moon and stars hang in the trees like lamps" (45). The forest represents Story and its inhabitants are living in Story, since "character is character and subject to its proper punishment; tampering with endings can disturb the forest's delicate balance" (11). In the middle of Reaper's forest and of countless legend stands a glass mountain,

the very emblem and embodiment of purity. A such, it represents not merely escape but also transcendence, the desire for which is said to be the deepest of humankind's desires and the source of its strange magical systems. . . . [For] many, drawn by the seductive thrill of going where no man has gone before, the prospect of this conquest (some think of it as liberation) may be sufficient. But for those of a more soulful bent, there is also a need for illumination and self-understanding, which is not to say, an understanding of the universe itself wherein for a short time one resides. Thus it is that the transcendent merges with the erotic and the manly in the heroic effort to pit one's strength and will against the mountain, to assail the unassailable. (46)

In that forest, punishments and executions take place at a special site: "It is called locally the Place of Entertainment, and not irreverently, for this drawing together of the community is the true and ancient meaning of 'entertainment,' execution its classical and most hallowed form" (62). Coover's punning here with the term "execution" is but one example of his elegant word games in his attack on fossilized patterns and defaults, in his plundering of the Grimms' fairy-tale treasure trove. As reviewer Rick Kleffel states: "Stepmother showcases some of the finest humorous writing you're likely to find. Coover's sentences are clear, punchy and light as a feather. Stepmother is the kind of book that you'll want to read aloud. . . . Coover's Stepmother is a wicked hoot that rides away on a broom from any expectations you might care to bring with you." 16 Which is precisely what Stepmother does at the end of section 4 when she commands her daughter, "Hand me that old straw broom, dear, and climb on. We'll leave by the chimney" (29).

Stepmother is only 90 short pages long, well, actually only 80, since ten pages are filled with Michael Kupperman's unusual illustrations. 17 All the more formidable the sweeping array of fairy-tale material compressed into such brevity and the verbal humor linking the different plotlines: the challenge is for the reader to follow all this, to witness the trope of the Stepmother—and that of the stepdaughter, for that matter—turned on its head and at the same time have a ton of fun reading along. During a rather casual-ironic chat between Coover and his former student Gabe Hudson, the latter asks his professor: "I want to know about this thing you have with fairy tales. Here comes Stepmother, right out of that old dark oral past. What's the lure?"

Kid lit. Fairy tales, religious stories, national and family legends, games and sports, TV cartoons and movies, now video and computer games—it's a metaphoric toy box we all share. Sometimes all this story stuff feels like the very essence of our mother tongue, embedded there before we've even learned it, so much a part of us that we forget it didn't come with the language, but that someone made it up and put it there. The best way to expose that and free ourselves up is to get inside it and play with it and make it do new things.18

Parallel to the metafictional rollercoaster ride through fairy-tale land, the "new thing" Stepmother is calling attention to is the fact that in the ur-forms of the classic fairy tales sex was present, yet did not serve to suggest sexual stimulation but, quite the opposite/contrarily, was almost always connected with violence. "Some may find the representation of sexual violence in the novella disturbing, but, far from titillating, those scenes work as a call to wake up from the complacency with which violence is sexualized in our culture. This book is hilarious, devastating, tender, and brilliant." .19

Consequently, the culmination—in order to avoid the fraught term "climax"—of the novella is a dicey seduction scene in which Stepmother tries to prevent Reaper from enforcing the daughter's death sentence. He recognizes her efforts, and plays along for the sake of appearance, because in his world it is clear: "Things will happen as they must" (88), and thus he prevents Stepmother from being at the scene, while she believes that according to the laws of the forest, no execution can take place without the Reaper's presence. "Not all legends are true," is his laconic reply. Stepmother has been duped by her archenemy, all her magic powers are of no avail. "I am filled with such a frenzy of fury, fear, revulsion, despair, chagrin, I can hardly think" (88). Her daughter is rolled down the hill in barrel with holes.20 and Stepmother arrives too late. Yet she already predicted that much at the beginning of her story, when in the first paragraph she talks about the Reaper and her keeping the cycle going, "rolling along through this timeless time like those tumbling nail-studded barrels" (2). But now, out of disappointed rage she transforms all the spectators into stone, all the while knowing that her magic spell will not last for long. "Fairy tales argue for an artistic model of continuity instead of revolution, of the collective rather than the individual; all influence, and no anxiety about it."21 Certainly not in Coover's novella: not only does he turn upside-down the character of the Stepmother—from malevolence to benevolence—but he also inverts the fairy tale's basic plot line—continuity—and foregrounds the story itself, and the act of story-telling. And thus the final, surprising sentence of a text filled with violence, rapes, torture, atrocities, mutilations, and sex in every imaginable (per)version, comes from Stepmother: "I share this with the Reaper: happy endings" (90).

Endnotes

1. To be published by Dzanc Books in September 2013 in their rEprint Series in eBook form.

2. "Inside Robert Coover: Ancient Myths in Modern Fiction." Issues Monthly, 16.2 (April 1985): 16.

3. Benson, Stephen. Cycles of Influence: Fiction, Folktale, Theory. Detroit, MI: Wayne State Univeristy Press, 2003. 159. In his erudite study Benson examines "the extent to which Coover's use of the fairy tale can fruitfully be placed within the context of a pragmatics of narrative" (148), and states that Coover "is concerned with the idea of the tale as an ideologically coded form of narrative . . . as a pervasive form of popular culture" (148). Less based on continuity, "Coover's is an aesthetic of mutiple disruptions, but one deeply informed by a concern for the human propensity to use narrative as an ordering system, a means of reading the real" (148).

4. Bacchilega, Cristina. Postmodern Fairy Tales: Gender and Narrative Strategies. Philadelphia, PA: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1997. 47.

5. Iftekharuddin, Farhat. "Interview with Robert Coover." Short Story, 1.2 (Fall 1993): 91.

6. Jack, Zipes, When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition. New York: Routledge, 1999. 1.

7. Amanda Smith, "Robert Coover," Publishers Weekly (December 26, 1986): 44–45.

8. Alma Kadragic, "Robert Coover," (April, 1972) Shantih, 2.2 (Summer 1972): 60.

9. Miller, Laura. "A Tone Licked Clean: Fairy tales and the roots of literature." Harper's Magazine, vol. 325, no. 1951 (December 2012): 84.

10. In his introduction to a public reading of "The Invisible Man" (from A Child Again, 2005), at CalArts MFA Writing Program Visiting Artists Series, October 18, 2005.

11. Using as his general frame story the Cinderella fairy tale, here is the list of the others brought into play, following the numbering system applied to the Grimm Märchen: All-Kinds-Of-Fur, Little Brother and Little Sister, Brother Lustig, The Blue Light, The Girls without Hands, The Story of the Youth Who Went Forth to Learn What Fear Was, Thumbling, Old Hildebrand, Iron John, The King of the Golden Mountain, The Robber Bridegroom, The Singing Bone, The Drummer, The Strange Musician, The Willow-Wren and the Bear, The Devil's Sooty Brother, The Goose-Girl, The Crystal Ball, The Six Swans, The Seven Ravens, The True Sweetheart/Bride, The White Bride and the Black One, The Twelve Brothers, The Three Little Men in the Forest, Fitcher's Bird/Fowl, Frau Trude, Hans the Hedgehog, How Six Men Got On in the World, Snow White, The Juniper-Tree.

12. Bloom, Harold. "Gardens of Unearthly Delights." [Rev.] Marina Warner, Stranger Magic: Charmed States and the Arabian Nights. Illustrated. 540 pp. The Belknap Press/Harvard University Press. $35. NYT Book Review, CXVII.13 (March 23, 2012): 9.

13. Benson, Stephen. Op. cit. 155-56.

14. The German term "lustig" can mean funny or jolly but also lustful, lusty, sensual. Coover most likely is well aware of both meanings and plays with the latter, even if, or just because the Grimms intended only the former.

15. Miller, Laura. Op. cit. 85.

16. Rick Kleffel. [Rev.] Stepmother. By Robert Coover. Rick Kleffel's The Agony Column," October 4, 2004.

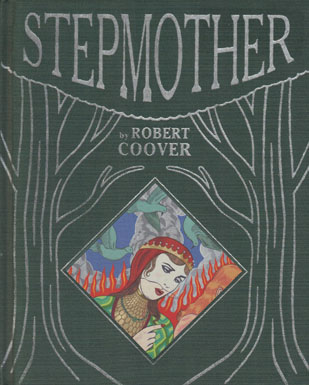

17. Stepmother looks like a traditional, expensive fairy-tale book: no dust jacket, cloth-bound in a dark-green hue, hand-stitched, on the cover a cutout picture of a queen raising a warning finger to a daughter disappearing into the frame, all entwined by a silvery forest; inside: large print on thick paper, with 10 tricolor, suggestive illustrations by Michael Kupperman's wood-cut art.

18. Gabe Hudson. "Notes on Craft: Some Instructions for Readers and Writers of American Fiction. An Interview with Robert Coover." McSweeney's, June 22, 2004. [online]

19. Cristina Bacchilega [Rev.] Stepmother. By Robert Coover. Marvels & Tales, 22.1 (2008): 198.

20. An example for Coover's extensive knowledge of the Grimm fairy tales: a similar fate awaits the antagonists in several of their stories, The White and the Black Bride (KHM 135), Little Brother and Little Sister (KHM 11), The Twelve Brothers (KHM 9), or, the maid servant in Goose Girl (KHM 89) in an identical situation, "to be stripped stark naked, and put in a barrel that is studded inside with sharp nails. Two white horses should be hitched to it, and they should drag her along through one street after another, until she is dead."

21. Miller, Laura. Op. cit. 86.

-------------

Elisabeth Ly Bell, German-born Visiting Scholar at Brown University's Literary Arts Program, with an M.A. in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. from the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at the Free University of Berlin, Germany. Her primary interest is in contemporary American fiction, and her teaching includes creation myths, fairy tales, and topics in American culture. Her scholarship on Coover has been published in Delta, Critique, and Review of Contemporary Fiction; she has also reviewed Coover's works for The Brown Community Bulletin and American Book Review and was interviewed on transferring literature to film in George Street Journal.

She also contributes to this issue:

"Robert Coover and the Neverending Story of Pinocchio,"

"HYPERBOXES, HYPED BOXES, ÜBER-BOXES,">

and "The Notorious Hot Potato".

|