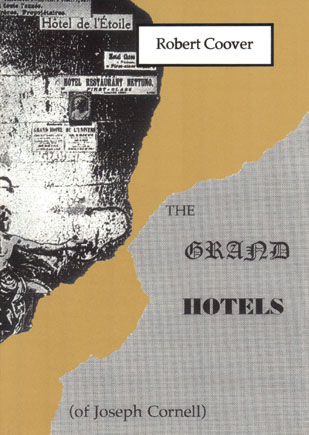

Burning Deck Providence, RI, 2002 $50 (signed cloth), 64 pp. $14 (paperback)

Robert Coover's new book, The Grand Hotels (of Joseph Cornell), is rather brief, just 54 pages of actual text and each of its ten stories has a headline beginning with "The Grand Hotel." Now, the artist Joseph Cornell, famous for his box constructions, created several series with "Hotel" names. So here comes Coover and takes Cornell titles, but not those of the hotel boxes; instead he uses titles from other Cornell art works, even from one of Cornell's films. At the same time, Cornell gave telling titles to his boxes, but then the named object does not appear in the construction, leaving it to the spectator to complete the associations. With Coover's hotels it's the reader's job. What the reader gets in one small book are two great magicians working with boxes; Cornell was interested in white magic, Coover presents verbal magic pure. Take Coover's first installment, which begins: "The Grand Hotel Night Voyage, described in its brochure as 'a soaring tower of dreams and visions for transient romantics with repressed desires and eventless lives,' is the archetypal grand hotel, first of its kind and said to be the progenitor of all others." And then it continues with: "Originally designed as a colorful hot air balloon (thus its name), it acquired its pagoda-like tower—at the time still under construction—as a consequence of an unexpected descent, although the lobby, with its caged tropical birds, its musical fountains, and its bright yellow walls, lined with mirrors, movie posters, and paintings of dancers and acrobats, retains still some of the lost balloon's original charm and gaiety. Indeed, this chance encounter of balloon and tower, … not only brought the Grand Hotel Night Voyage into existence, but fortuitous juxtaposition became a standard requirement for grand hotel classification thereafter." (9-10)Here we have it, right from the start: Coover condensed, Coover at his best. Never mind the title play ("Night Voyage" was the title of a 1953 Cornell exhibit,) or the reference to Cornell's fascination with huge balloons, or, the very prominent word-pagoda in a Cornell work; these references are just details for a player's inventions. More pertinent is what the author says about his new stories on the book's back cover: "they are also an 'architectural portrait of the artist,' with biographical information 'built into the construction of the text like girders, brickwork, or decor'." In just three paragraphs, this opening into the hotel stories not only lists a major Coover theme, "fortuitous juxtaposition"—of which there is none, neither in Coover nor Cornell, for that matter—but also introduces an architect who shares with Cornell "dreams and visions for transient romantics," "repressed desires and eventless lives," "dedicated and solitary explorers." This first short story furthermore itemizes Cornell's method of perpetual reconstruction of his works, his preferred colors, and the impressions his boxes make: "the comforting shadows of the intricately compartmentalized interior, with its ancient twisted staircases that rise and fall like heaving waves, its muffled whir and whisper of dreams past seeking to reconstitute themselves," and those hotels/boxes with their "full range of scientific and whimsical instruments, mechanical devices." (11) Joseph Cornell's boxes are hybrids of collage and diorama, his ultimate subject being the creative mind itself, while Robert Coover's mansions of the mind, with their shifting boundaries of time, space, age, and movement, are also a meditation on art as an architecture of the imagination, a meditation embedded in the delight of mixing the concrete and specific with the impossible (impossible in this world, at least). Yet, although they are approaching their subject matter from separate angles and different disciplines, the idea of space and architecture in both Cornell and Coover is about evocation, about building from and for the imagination. Cornell's emptiness, especially in his later box constructions, invites the imagination in. While Cornell is a miniaturist, "a virtuoso of fragments, a maestro of absences," 1 Coover often favors elaborations, big structures, even though he always stays close to the tale, a small structure. Some of the fascination of Cornell's work seems to come from a tension between size and what is suggested or depicted: one has the sense of an entire world being contained, or an essence of the world being distilled. Cornell's art attempts to exclude, while at the same time it contains portions of the whole world. Coover works differently but perhaps with the smaller goal of creating a world which may refer to the world as we know it, but is primarily itself, an object. What happens in the works of both men is that the world "inside" begins to be defined by its own rules. If the truth of a building comes from within, Coover's supple flow of space as well as his spatial transitions from compression to expansion invite lingering. His Grand Hotels are three-dimensional structures brought onto paper, translated into words by a pure virtuoso of design, thinking in geometry. Coover's stream of geometry flows into possible and impossible directions; in his composition of curvilinear forms and structures, in his spatial configurations, architecture becomes a new art. In the second story, matters get more multi-layered, when Coover presents numerous connections to different Cornell works by naming this hotel Penny Arcade. Cornell produced several works of art with this title, of which the most famous is dedicated to the actress Lauren Bacall. Still, passages like "Is she … alive, or is she some kind of automaton, a projection, in effect, of the architect's fantasy? And if alive, how did she come upon her strange fate," or, "an ineffable longing for a past, almost as if she had ceased being a structural component of his architectural inventions and had become the object, in a word, of his amorous obsession" suggest that the frame of reference would rather be Cornell's Penny Arcade series dedicated to Joyce Hunter, who even after her death was of obsessive importance to Joseph Cornell. Coover phrases it this way: "he wanted her to remain forever universal and timeless." (15) He ends this story with "the architect, who is not known to have constructed anything since the Grand Hotel Penny Arcade, a tragic estrangement," (16) and with that line returns us to the biography of Cornell, who stopped making boxes in the late 1950s. Yet the overall theme of Coover's "The Grand Hotel Penny Arcade" is what the title refers to: those slot machines in the game arcades around Times Square, one of the principal symbols of Cornell's childhood pastimes and reveries. It is not exaggerated to assert that Cornell, a hugely repressed individual, had a fixation on everything childhood, that the purity and innocence of childhood and the "child within" were of tremendous importance to him, that in both his private life and his art, he longed to recapture an emotional essence of that time and its experiences. Yet, under his relentless gaze, childhood was an asexual time, and his ideal female was a child, like his creation Bérénice, the young girl in "The Crystal Cage (Portrait of Bérénice)." One scene, the image showing Bérénice standing outside, peering into the window of her Chinoiserie pagoda, is accompanied by this text: "Bérénice of 1900 gazing into her own past and future," thus pointing out the title's seeming contradiction between crystal and cage. Coover uses all the references. As the fifth hotel, for instance, he presents "the most popular of all the grand hotels," (28) enclosed inside a lesser one from which voyeurs observe people reliving their often fictional childhoods, a situation rendered in typical Coover fashion when "watchers watch the watchers and the watched as well." (30) In this context, one curious aspect needs mentioning. Robert Coover, who is not particularly known for chastity or for a lack of carnal encounters in his writing – just watch out for Lucky Pierre! – chooses Joseph Cornell, who presumably died a virgin, who never capitulated to his desires but sublimated lust and longing into highly associative, poetic image making, a process he called "explorations." Coover's transformations of the Cornell material play with the artist's inhibitions by sneakily inserting a Cooverian twist, as in "The Grand Hotel Penny Arcade," where the rooms give off "the faint sweet smell of youthful flesh, where the guests find "each room with its own individual coin-operated peephole viewers, viewers technically augmented by manual zoom lenses, tracking and lock-on mechanisms worked with a crank, and simulated kinetoscopic flickering." (13) Just as there is no lust or sexuality in Cornell's art, there is also (except for one case) no violence. And Coover makes use of this fact as well, when he describes his fifth hotel: There is probably no hotel in the world more chaste in design and policy with respect to children than the Grand Hotel Nymphlight, none more devoted to innocence, purity, and simple childish delight … and though murder, rape, war, cruelty, torture, beatings, abuses and horror of every sort are common experiences of preadolescence everywhere, there's little of any of that here either, unless specifically introduced in the memorabilia of a guest, for these things are of the world without, not the child within. (31) At this point it is useful to ask: What is it with these Grand Hotels? Why hotels? There are the regular hotels—providing lodging, meals and other services for the accommodation of travelers or semipermanent residents—and then there are the grand ones. First off, a definition of this special type of building for the powerful and the rich, the Grand hôtellerie, which saw its rise and fall between approximately 1830-1930: The magic of grandeur and luxury … required two basic components: architectural design on the one hand and practical but sensitive management on the other. Development of theatrical qualities was necessary in both these fields for the grand hotel to attract and maintain successfully a starry – and wealthy – clientele to act on its stage. In a world both real and unreal, the hotel culture of the nineteenth century evolved its own pattern of behaviour. … The public background that the grand hotels provided was thus a paradoxical element, giving opportunity for changes leading ultimately towards decline in formality and splendour. 2Late in the book, Coover defines them his way: "Mere popularity, of course, does not by itself confer grand hotel status. This is achieved by architectural harmony and brilliance, high standards of service, novel décor, unique special features, …the creation of surprise and wonder, dependable plumbing." (51) With Coover we get hotels within hotels, and inside those we are often allowed only into the public spaces, usually at nighttime. But there is this extension to Coover's title, the "of Joseph Cornell." Does the reader of Robert Coover's The Grand Hotels have to be familiar with Joseph Cornell, his life, his work, with Cornell's hotels? One certainly can enjoy the Coover vignettes on their own, but it would greatly enhance the reading pleasure to be in the know, in fact, to know pretty much everything about Cornell, both his life and his works. Then again, it might suffice to know about Cornell's hotel boxes, mostly produced in the 1950s. The grand hotel culture's aspect of juxtaposing reality and illusion made them a life-long topic for Cornell: at my last count, 32 of Cornell's boxes thematize hotels, 10 are about grand hotels, and four other ones are mentioned in his diaries. That's quite a pool to choose from. The The Grand Hotels' cover design by Keith Waldrop uses a Cornell hotel, the dedication names one, yet Coover doesn't. None of his grand hotels takes its name from a Cornell hotel. Still, they sound so Cornell, and, in fact, they are. Maybe with the exception of Edward Hopper, hotels have not been a major topic in art history. Hopper's rooms and Cornell's hotel associations are similar in spirit: in both Hopper's and Cornell's hotel scenes, the prevailing mood is loneliness and (romantic) yearning. Neither portrays luxurious hotels. If Cornell's hotels, despite their grand names, are often shabbily charming places, Coover's are quite different. His fictive accommodations are imaginative, entrancing, virtual hotels, not so much transient places but settings for private and anonymous brief encounters and/or assignations, where the most unusual services are being offered, where in one hotel the guests are served by birds. With four of Coover's ten stories touched on, the prospective reader of The Grand Hotels can hardly fail to perceive that while Coover's range and juggling are at their prime, his imaginative trickery and verbal mastery have reached a new stage. These stories, with or without knowledge of Joseph Cornell, are luminously beautiful and at the same time strictly organized in their union of subtlety with the riot of comic imagination. While many of Cornell's boxes are almost empty, Coover's overflow with words, fantastic allusions, illusions and metaphors. And thus it must be tongue in cheek, when Coover, master manipulator of metaphors, has the narrator of "The Grand Hotel Nymphlight" remark: "That's more likely just another fantasy of the popular press, one metaphor propagating another in the common way." (30) Nothing at all is common in these vignettes, not even for readers familiar with Coover's style. In these stories he can be lyrical, gentle, even if once in a while his mischief and wicked humor break through. It's a lot of fun and a true delight to follow where Coover takes the reader on his Cornell trail. To be sure, Coover knows his Cornell inside out. Not only are there several Cornell boxes with references to as many as four hotels inside a single box construction, but in story number 6, "The Grand Hotel Crystal Cage," Coover even hints at a destroyed Cornell object, entitled "The Crystal Palace." The fictive architect here creates a glass so clear that the hotel built from it can neither be seen nor found. After long experimentation, its designer has "developed glass so transparent that … one saw not the objects, people, streets, or landscapes on the other side, but their inner truth and being. … One not only saw through them, one saw beyond" (38-39) - seeing through reality, even beyond, into the void. As for watching Robert Coover: for his 1991 pioneer project at Brown University, a "hypertext fiction" workshop, Coover invented the title metaphor "The Hypertext Hotel." A more theoretical expression of his interest in a new type of literature developing with the rise of digital media can be found in a series of seminal essays for the New York Times Book Review in the early 1990s, then there was "Stringing Together The Global Village" for the While Coover aficionados are eagerly awaiting the publication of the big Lucky Pierre-opus he has been working on for more than 30 years—now scheduled for October 2002—and while several new short stories have appeared since his 1998 novel Ghost Town, all of them typical Coover fare, this spring saw a different (a softer?) side of Robert Coover: the ten vignettes, of which the first five previously appeared in a remarkable and visually beautiful anthology, A Convergence of Birds: Original Fiction and Poetry Inspired by Joseph Cornell. Not only birds now, also convergences of a different kind.

Rewind to Joseph Cornell [1903-1972], the American box artist, from Queens, NY; a sculptor, painter and filmmaker, the creator of assemblages, celebrated by the Surrealists as one of their precursors. His best known and most characteristic works are highly distinctive "boxes" - simple wood-boxes, usually glass-fronted, in which he arranged and juxtaposed surprising collections of photographs with fragments of objects (e.g., shells, balls, butterflies, feathers, bottles, maps, stars, pieces of wood or fabric) to create a symbolic meaning. These boxes look like miniature stages or theaters, quite beautiful and mysterious. "Theaters of the mind," they have been called, or "boxed works of poetic art." This spring, when NYC's MoMA was showing "Surrealism: Desire Unbound," an exhibit dedicating a whole room exclusively to Cornell's artwork, he would not have agreed with this categorization; he did not want to be America's one homegrown Surrealist, he wanted to be called an American constructivist. Even today, 30 years after his death, art historians and critics have not been able to place Joseph Cornell within a particular movement: whether Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism, Pop Art, or Minimalism, he was always already there and never belonged to any movement. What a peculiar man, devoting his whole life to the medium of assemblage, transforming junk into art, becoming "the most undervalued of valued American artists." 4

Are we in hyperfiction land yet? Yes indeed, Cornell can be (and has been used as) a model for hypertext, he might even be beyond it, since he "uses his elements as though they were words, but what they allude to have no verbal equivalents." 5 Yet the more interesting aspects for Coover's work appear to be Cornell's associative networks, the possibility to chart links and interconnecting threads, and then to use simple gestural forms in a dynamic way for sculptural objects, to fill an imaginary architecture with new expressive energies. When making use of Cornell's uniqueness and his poetic ability to employ "symbols, suggestions, allusions to build metaphors, to create drama, to evoke mystery," 6 Coover is dealing with projections, connecting architecture to hypertext, or hypertext to architecture, and moving beyond.

As pointed out earlier, and even though Coover claims so in the beginning and towards the end of his collection, there is no "fortuitous juxtaposition," neither in Cornell nor Coover. Instead, these hotel stories are of utmost control and stringent design. In them, it is true, Coover brings certain hypertextual processes onto the page, but he does not need a computer, a monitor or links, and it works much better (t)his way. Who needs hypertextual window-dressing when one can have prime Coover on 54 sparsely filled, yet immensely dense pages?

Coover's last story is "The Grand Hotel Home, Poor Heart," a title taken from a Cornell collage. Joseph Cornell's title, in turn, refers to the 1795 poem "To Nature" by the German Romantic poet Friedrich Hölderlin, of whom he liked this beautiful passage very much: "home, poor heart, you cannot rediscover if the dream alone does not suffice." The back cover of The Grand Hotels (of Joseph Cornell) informs the reader that the ten vignettes contained are "exploring the nature of desire and the melancholy of fulfillment." But in the penultimate sentence Coover has his architect sum up his goal more appropriately: "Quiet consolations, sudden joys, touches of beauty." (62)

Robert Coover, The Grand Hotels (of Joseph Cornell). Providence, RI: Burning Deck, 2002, 64 pages, cloth $25, cloth signed $50, paperback $10.

1. Ratcliff, Carter. "Joseph Cornell: Mechanic of the Ineffable." In Joseph Cornell. Edited by Kynaston McShine. Published on the occasion of the exhibition "Joseph Cornell," November 17, 1980 – January 20, 1981. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1980), 43-67, p. 43.

2. Denby, Elaine. Grand Hotels: Reality & Illusion. An Architectural and Social History. London: Reaktion Books, 1998. P. 8-9.

3. Helbing, Brigitte. "Die hohe Kunst des Zappens. Der Hypertext zwischen Buchdeckeln: Robert Coover's Roman "Johns Frau." Berliner Zeitung (19. Juni 1999).

4. Soloman, Deborah. Utopia Parkway: The Life and Work of Joseph Cornell. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1997. P. xxi.

5. Porter, Fairfield. "Joseph Cornell." Art and Literature, no. 8 (Spring 1966): 120-130. P. 121-122.

6. Myers, John Bernard. "Cornell's 'Erreur d'ame'." Joseph Cornell. Catalogue of the exhibition "Joseph Cornell," May 3-31, 1975. ACA Galleries, New York. New York: Barton Press, 1975. P. 3-15, p. 11.

Bell, Elisabeth Ly. "Hyperboxes, Hyped Boxes, Über-Boxes." American Book Review, vol. 24, no. 3 (March-April 2003): 11-12.

|