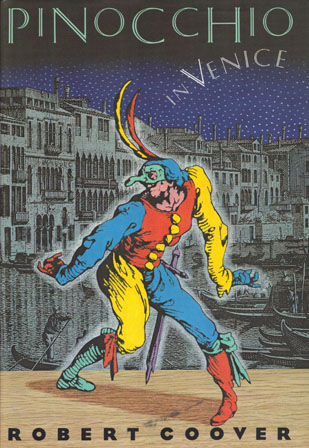

Interested in interdisciplinary dialogues about the future, Robert Coover has from the start of his career made expert and mischievous use of the archives of Western culture. He has consistently dealt with archived texts, from the Bible to classic fairy tales, from creation myths to standard American myths (small town, the Western, sports, history, movies), and has topped all this with a seminal essay in 2007. Nowhere has Coover expressed more poignantly and wittily how he envisions his role as a writer than in the seven, dense paragraphs of "Tale, Myth, Writer." This allegorical essay deals with the writer's subversive struggle with myth, falsehoods, dogmas, confusions, all the debris of the dead fictions as well as the creative impulse to combat myth; it is at once a performance and a definition of a performer. The text's central metaphor is that of a house—in fact a stately mansion, with closed curtains, locked doors and dark attics; with Myth the master, Tale the ally in Myth's mansion and, as Coover suggests, its "castle keep," and the Writer, too, staying inside. But the Writer is looking for exits, ways out, even if they turn out to be false leads. This architectural image is ideal, since it provides Coover with numerous corollary metaphors, all related to a house: neighborhood, inside/outside, interior design, unreliable employees, tour guides, ownership and maintenance, renovation and possible destruction. But the metaphor also allows for the transgression of limits, for trespassing, break-ins, uncovering hidden things, even discovering concealed origins. It's the writer's job to challenge boundaries. Disgruntled about being interviewed, Coover remarked: "There are only ten possible questions, and they've all been answered. You can look them up; you don't have to bother the author. Homer got asked all of them, and what he said was, 'Why are you asking me all these old questions? Go read the walls of Uruk. I'm an old man and I'm blind and I don't have to do this anymore.'" (Hudson interview) Referring to the walls of Uruk, Coover harks back to the Western world's first literary production, to The Epic of Gilgamesh, which is archived/preserved on clay tablets, probably a smarter and more lasting medium than today's computer storage devices. In his fictions, Coover always goes to the roots and deals with institutionalized fictions on their own ground, but this Coover essay provides an interpretive key to the dynamics of writing and opposition. "Part of the writer's task is to absorb the mythic content of his time and wrestle with it on its own ground. (When we say a writer is always a part of his own time, we mean that though he may transcend his society, society is also and above all within him.) Yet transcendence of the social myth has always been a part of what the writer is doing, from Gilgamesh on." ("Tale, Myth, Writer," Draft) The essay is framed by the Consciousness Industry, within which Myth and Tale, in their various guises, flourish. That industry's powerful role is what the Writer is up against, because it, like Myth, celebrates mental, moral and aesthetic stupor, and at the same time profits from its products, since mindless-ness and status quo sell so much better than innovation and challenge. And the Writer is a clown, not the tragic hero who doesn't get up again after he falls, but the uncivil clown, amoral and capable of outrageous mockery, who can be a serious figure, privileged because—and therefore—faithful. Only the Jester can tell the king the truth without being punished. And his tool against power, not an option in myth or fairy tale, is irony, which Coover calls a gift. Just as an archive contains stored knowledge, so too does a computer, using mathematical functions, just like a math book. The latter figures in a certain childhood classic as it does in a Coover novel, where it appears in its contemporary form: a portable computer. Over a hundred years old, his story translated into more than eighty languages, Pinocchio is still poking his nose around in all kinds of animated and illustrated versions. Yet the original by Carlo Lorenzini (later using the pen name Collodi, after his mother's birthplace) was not from the beginning intended to become a book, but first appeared in a magazine for children in July 1881, as two chapters of the "Storia di un burattino." And only because these stories were so successful and the young readership so eager to learn more about the puppet's adventures did Collodi, after 15 chapters, rename his work Le avventure di Pinocchio (The Adventures of Pinocchio, 1883). It is a story of growing up, of an education in social adaptability. But it is also a sad tale of loss: the dying away of the child's ability to talk to and understand animals, the disappearance of the realms of wonder, magic, and the fairy, the loss of anarchy, creativity, genius and grace. Not a single one of Collodi's grown-ups represents a world worth growing up into. Nor do they in Coover's 1991 adaptation and updating: Pinocchio in Venice. His is a fantastic, sad, and wickedly hilarious story. It reads in part like a comedy thriller, a crime novel, a treasure-hunt story, a riches-to-rags reversal—the luck-and-pluck formula of the American dream upended—a fairy tale gone awry and bawdy, a collection of pratfalls and slapstick routines, an upended initiation story, a treatise on the "usefulness" of knowing and the work ethic. This novel's extravagance makes Rabelais look like a junior reader. And it is great fun to read; Coover's Venice is indeed worth the trip. In order to see how comprehensively and at the same time how maliciously Coover makes comic use of his material, it is a must to read the original Pinocchio. Kitsch versions should be disregarded, including the Disney adaptation. All the latter suppose that children cannot deal with absurdity, incongruity, and subversive fun, and instead should be fed only a watered-down, extenuated version which must be pedagogically constructive. It is the original story of Pinocchio that Coover continues and enlarges, and only knowledge of the original Collodi childhood tale allows the reader to appreciate fully what Coover accomplishes in his sophisticated version. In the opening scene of Pinocchio in Venice, and in verbatim quotations throughout the novel, as well as in the protagonist's academic development, Coover uses another archived classic, Thomas Mann's 1912 novella Death in Venice. Gustav Aschenbach's infatuation with and description of young Tadzio is paralleled in Prof. Pinenut's longing for the Blue-Haired Fairy. All of Pinenut's books are titled after publications by Mann himself, or by Aschenbach, and, as always, Coover renders these titles in most ironic ways. Collodi's Pinocchio starts as an artifact and becomes an artist. This is probably most apparent when he meets other artists, when he appears to the marionettes like a long-awaited savior (and does save Arlecchino from death), when they welcome and celebrate him. But then Pinocchio leaves the theater to make the whole world his stage, only to give up his freedom in the end, after so many pranks and adventures, in order to become a real boy: nice and good. Collodi's technique of portraying the final stage in Pinocchio's development less as a culmination than as a painful loss breaks up the outer structure of this "educational" novel and undermines it from within. Thus, despite moralism, sentimental and even kitschy pedagogy, the lure of shenanigans and adventure, the totally unreasonable experience of primal joy have for more than a century seduced children of all ages, among them director Federico Fellini and writers Italo Calvino and Robert Coover. The latter picks up the story of Pinocchio with the question children worldwide have pondered: what happens after the wooden puppet becomes a real boy? And Coover answers this in detail through over 300 insinuating pages. When the novel begins, Pinocchio is almost a century old. Having gained artistic inspiration from his father's mural in that tiny natal hut, Pinocchio becomes an art-history professor in the United States. He also briefly tries out his talents as a painter, but aborts this career because of metaphysical and physical happenings at his office. From that point on, he better understands "the tragic decline of art" (234). In 1940 he assists a Hollywood film-team shooting a "semi-autobiographical" version of his life. Honored with two Oscars—as was the 1940 Disney film Pinocchio, which Coover exploits exuberantly—the movie's success brings Pinocchio into the company of movie stars and actresses. In spite of all the celebrity, he remains a literary man and his life's goal—after seven "classics of Western letters" (47), seminal studies, and numerous other publications and lectures—is to complete his eighth book, Mamma. This is to be his capolavoro, his all-encompassing masterpiece. The esteemed scholar, il gran signore, the distinguished emeritus professor from abroad, the world-renowned art historian and critic, social anthropologist, moral philosopher, and theological gadfly, the returning pilgrim, lionized author [...], native son, galantuomo, and universally beloved exemplar of industry, veracity, and civility, [is] not a child of his times, but the child of his times. (47)When the narrative begins, he thinks he has rounded off his eighth book with a final chapter entitled "And the Wood Was Made Flesh and Dwelt among Us" (281). At his campus office toward the end of Christmas break, however, he realizes that his life's work will be incomplete without an additional closing chapter. In order to write this final chapter he hastily hops on a plane, armed with Petrarch's Epistolae Seniles and his computer, and flies to Italy, back "to his, as it were, roots" (14). He arrives in Venice in January, in time for the carnival season. There he meets again most of the characters from his childhood, who have grown old just as he has. Basically, Coover's novel relates Pinocchio's adventures with these old acquaintances (enemies and friends) and his attempt to complete the missing chapter for Mamma. The story's first two parts, "A Snowy Night" and "A Bitter Day," describe the old gentleman's initial two days in the streets of Venice, mainly in the quarters San Polo and Dorsoduro. Only later does he leave these areas for the better part of town, San Marco. Before the book's third part ("Palazzo del Balocchi"—the Palace of Toys) picks up, there is a temporal interruption caused by the Professor's blackout and the resulting fever dreams. He is sheltered and cared for by Eugenio, who owns and inhabits the Procuratie Vecchie. Cured and restored to consciousness, he next experiences ever more traumatic events from Sunday morning to late night on Monday, one week before the climax of the carnival festivities. The narration skips this whole week. "Carnival" then, is the fitting title for the fourth part, which spans the period from Monday morning to just before midnight on Mardi Gras. Finally, the conclusion, "Mamma," has just one chapter, "Exit," and takes place during the early hours of Ash Wednesday. Such straightforward geography and chronology, unsurprisingly, is not offered by Coover, who makes a game of challenging the reader to keep track of all the reminiscences and retrospects, sometimes layered, interrupting and/or complementing each other. Almost half the novel is told through flashbacks. The fun as well as the function of this technique for both Coover and the reader lie in reverting to the original again and again. Coover uses complete scenes and in fact quotations, dialogues in particular, verbatim from the Ur-Pinocchio and thus, Coover's Pinocchio sheds new light on Collodi's. Venetian Acquaintances: From the very beginning, right after his arrival at the Venice train station, the jet-lagged Professor Pinenut has deep forebodings; yet, just like young Pinocchio, he disregards them. Thus, when he encounters a strange porter and next a tourist clerk, both in carnival costumes, he dismisses all the obvious facts, unwilling to believe that these are the two villains who have cheated and betrayed him before, the Fox and the Cat. And they fool him anew. They cross his path many times in varying disguises, even take him to the same restaurant, make him pay the enormous bill again, repeatedly rob him, and again leave him alone, freezing and lost in the winter night. The following encounter with a winged lion, however, has no parallel in Pinocchio's childhood, and it does not matter that Coover here fuses two distinct Venetian lions: the stone lion from the third level on Coducci's clock tower in St. Mark's Square and its bronze counterpart standing atop a column on the Piazzetta since 1174. Although the first meeting with the lion is a strange and threatening one to the old wayfarer, this creature nevertheless becomes his rescuer in a number of ostensibly hopeless situations throughout the story. The winged lion, centuries old, has been all over the world, and has seen it all: [...] now I know better. I know now this is the real Venice, has been all along, ever since that first desperate wanker, pissing himself with fright, nested here like a marsh bird a couple of millennia ago—no, fuck all the famous pomp and grandeur, the bloody glorious empire and all the tedious shit that went with it and made such strutting ninnies of us all, all that was just for show, a kind of mask the old Queen put on to hide her cankers and pox pits, her true face was back here all the time, just like the devil's true face is on his arse. (291)And he also knows who is now running all of Venice: Eugenio, the head of Omino e figli, S.R.L. The presentation of this particular figure shows how far Coover is able to push, play with and innovate from the original material. Collodi's Eugenio is a minor figure, appearing only once in episode 27. He is the one who is struck—supposedly mortally—by a math book during a fight among classmates. Coover's Eugenio, by contrast, is a major character with a full-fledged personal history: he too left home and school for Toyland, only his fate was not simply to turn into a donkey like Pinocchio and his friend Lampwick. He was raped by the Coachman and became his servant and lover. From the Little Man, "L'Omino," as the Coachman was called, Eugenio learned how to trick, betray and abuse others. But Eugenio ultimately avenged himself. He made the Little Man sign over everything, which is practically all of Venice, before his death. He has adopted the dead Coachman's sexual preferences, too, those "being mostly of the Tyrolean sort" (209). By the time Pinocchio arrives in Venice, Eugenio rules over a comprehensive empire and is not stopping at that. He presides over the police force and has absolute control of what is going on in the city. Already he resides in the palace of the Procuratie Vecchie right on the Piazza San Marco, which he has turned into an aristocratic retirement hotel, "catering to banking magnates, oil barons, the nobility, former munitions makers and Third World presidents, gambling czars and diamond miners, all the successful diggers and owners and traders of the world, now purchasing for themselves in their final days a foretaste of paradise in paradisiacal Venice" (200). He will soon own the Rialto Bridge, convert the Ponte dei Sospiri into a love nest, tear down and gentrify the entire Giudecca Island, turn the Arsenale into "a vast eighty-acre marina for the world's most luxurious private yachts" (204), and finally make his fondest dream come true: to top the Palazzo Ducale with a penthouse. Not only does Eugenio already own most of Venice and soon the rest of it, he also has gigantic plans for diverse, lucrative—because media-financed—festivities around the soon-to-depart, the recently-deceased, or the relics of the long-ago-martyred. To support his projects, he cultivates the ultra-rich, especially the elderly among them. And he is "nothing if not thorough" (292) in maneuvering to inherit what they own: if they refuse to die when it suits him best, Eugenio helps out or has one of his servants give them an assist. When he tries to have Pinocchio killed, the wise old lion comments on Eugenio's manipulations and at the same time gives an outlook on corpulent Eugenio's fate: "Don't mind your drowning these wormy old dog-cocks out behind the Arsenale, no one gets hurt that way, but dumping the turds in my Piazza is going to get some fat little sporcaccione stepped on!" (194) The first person the ex-puppet meets in Venice is one of Eugenio's subordinates—and many more cross the old scholar's path. There seems no limit to the power of the Little Man's gang. The only group not under Eugenio's sway is the subversive, anarchistic Puppet Brigade. These terrorists are Pinocchio's old friends, his wooden brothers and sisters from the marionette-theater days, who now earn their living as the "Great Puppet Show Vegetal Punk Rock Band," not unlike the "small troupe of street singers" Gustav Aschenbach encounters in Venice, and thus yet another reference to Thomas Mann's novella. When they meet again on the Campo di Santa Margherita, Pinocchio is caged in a wastebin and not at first recognized. Upon discovering his true identity, though, they rescue, welcome, and celebrate him just as they did in the old days when Pinocchio spent "the happiest night of his life" in their company (138). Since then, the puppets have been persecuted by Eugenio's police. Forced to go underground they are now hiding in commedia dell'arte costumes. They have developed a high degree of make-believe, sometimes so tricky that even Pinocchio cannot immediately tell which and how many figures are hidden beneath a disguise. In these varying roles, they accompany Pinocchio on his misadventures throughout Venice and repeatedly rescue him from entrapment. To his very last scene, the Burattini remain his true showbiz friends and ultimately enable him to "make a good exit" (313). The old pilgrim's only other friend in Venice makes a tragic exit: Alidoro, the police dog from his youth, whom Pinocchio saved from drowning at their first meeting. The mastiff has never learned how to swim. His lifelong fear of water earns him the nickname "Alidrofobo" (idrofobo is Italian for hydrophobic), and long before the fact he anticipates his own death in the Venetian waterways: "I'll fodder their boggy eelbeds in the end" (104). He finds a watery grave when he devotedly jumps into a canal, having picked up Pinocchio's scent, but almost blind, he fatally mistakes the aged scholar's fallen-off ear for the old comrade. Apart from the marionettes, only Alidoro really intuits why this traveler has returned to Venice. Yet he remains "a friend for life, a real friend, perhaps the truest one he ever had" (245), and protects Pinocchio, well aware throughout that the professor's quest for his book's final chapter will only lead to disaster. And he explicitly warns him of the Sons of the Little Man and of Eugenio in particular: "He's running the show now. You should've killed him." (110) That killing is exactly what happens in the chapter "The Fatal Math Book," when Pinenut realizes that/how all along Eugenio has betrayed and finally stolen everything from him. On Tuesday night, at the height of the carnival, Eugenio gives the old professor a present, "an all-too-familiar portable computer" (298). That very computer has already been mentioned on the novel's third page: "It is this magnum opus of his, in all of its physical manifestations (on the hard disk of his portable computer, on two sets of backup diskettes, and on voluminous printout, printout so edited and re-edited—he is nothing if not a perfectionist—as to resemble a medieval manuscript" (15). Pinenut, traveling from America to Italy, took good care to avoid damage, as "his computer is nested in polystyrene" (24). But "his current work-on-hard-disk" (36) is not safe from thieves. After he is robbed by the Fox and the Cat, he sobs to his canine friend about his losses: "All my bags—choke—my computer! My floppies! Oh, Alidoro! My life's work—!" (53) At first he is overwhelmed when his magnum opus is on his desk again, but once he comprehends that Eugenio had orchestrated the theft in the beginning, Pinenut is suddenly so filled "with an indescribable loathing, a hatred of what Eugenio had done to him, of what he had done to himself, and of his long wretched life so wrongfully spent" (299), that he throws his computer out the open window onto St. Mark's Square, onto the carnival crowds: "Free at last!" (299) When he looks down, he sees he has killed Eugenio, who is now "wearing the fallen computer like a large square cartoon head." (299-300) The fatal math book, indeed. When Alidoro brings his old friend Pinocchio to the boatyard's watchdog, Melampetta, she at first does not recognize who is being introduced and retorts, in a typical Coover mixture of biblical, Kantian, and otherwise learned philosophical mis-quotations, "No, you can sing all you want, squat-for-brains, you're just pounding water in your mortar, as Leucippus of blessed memory once said to William of Ockham over an epagogic pot of aglioli, there's no room at the inn nor in this shithole either, and that's conclusive, absolute, categorical, and a fortiori finito in spades!" (61) Much later, Pinenut thinks about his old friend Lampwick, "for, as William of Occam observed long ago, God could have chosen to embody himself in a donkey as well as in a man, and who is to say that he did not?" (192) Coover here plays not only with two philosophers who cannot have met, Leucippus of the first half of the 5th century BCE and William of Ockham (1287-1347), a prominent figure in the history of philosophy during the High Middle Ages, and with the fact that only a single fragment of Leucippus survives: "Nothing happens at random, but everything from reason and by necessity." He also allows himself a word game with Occam, the programming language named after William of Ockham. Betrayal and Insight: Notwithstanding the watchdog's misgivings about his "sacred mission," Prof. Pinenut pursues his life's goal with full remaining energy. It is not so much the final chapter to Mamma, his magnum opus, that escapes him; it is the Blue-Haired Fairy for whom he came to Venice. And he does meet her, although at first in the startling apparition of Bluebell, a vulgar, loudmouthed, gum-popping, dumb big-breasted blonde, a former student of Prof. Pinenut's. In fact, she finds him, just when the old gentleman thinks himself unobserved in the Church of San Sebastiano, daydreaming about his youthful initiation into sexual pleasures by the Fairy. Yet he does not recognize her, even though the Blue-Haired Fairy's goat suit—the legendary blue fleece he has chased after all his life—has turned into the American's "gaudy blue angora sweater" (123). And as with the Fairy, Pinocchio is both attracted and repelled by Bluebell's presence. Deep inside he knows she is an American barbarian; still, he cannot resist her spell. And as did the Fairy, she too entices him and fools him. But despite all his learning and wise old age, at heart he still remains the simple-minded wooden puppet and keeps hoping to the very end that this time his Fairy will not deceive him. Of course she does, just as Eugenio betrays him. For the secret assignation with Bluebell, "the august professor emeritus" "had asked for a proper philosophical costume, a mysterious and somber bauta perhaps with ruffle and tricorn and wig and cape" (270). What he ends up in, rather, is a whole-body donkey-suit made entirely of heavy pizza dough, baked to a firm crust around him in a bread oven. Only then, when he has been transported out into Piazza San Marco (which Napoleon once called "Europe's most sumptuous drawing room"), put onto a revolving platform like a peep-show object, just before the hungry mob gets Eugenio's signal to satisfy its "bestial appetite" (289) on his doughy hide, only then does he clearly recognize the double betrayal. After his final victory over the Fox and the Cat in the original, the young Pinocchio had thrown them three proverbs. Almost a century later in Venice, these three sayings are scrawled on the only page left to him after the theft of all his writings. The first one, "Stolen money never bears fruit," is turned back against him by the Fox and the Cat, who steal and publish Mamma with a final chapter of their own: "Money Made from Stolen Fruit." The villains print Prof. Pinenut's magnum opus at Aldine Press, an all-Cooverian double irony, since Fox and Cat indeed make money from their theft, as their work becomes a worldwide success and is reviewed in both La Repubblica and Corriere della Sera. On the other hand, Aldine Press is an ironic reference to the Venetian printer Aldo Manuzio (1449-1515), the leading figure of his time in printing, publishing, and typography. The second proverb, "The devil's flour is all bran," attains ambiguous meaning early on when Pinocchio talks to Alidoro about the strange desubstantiation symptoms that have befallen his body (106). A sarcastic turn of the phrase is presented to Pinocchio with the Fox's signature under her farewell letter to him: "Yours in the bran, La Volpe." (286) He grasps the proverb's full impact when he is baked in pizza-dough and paraded through the streets: "Ah, this, this [. .. ] is the devil's very flour [ . . . ] and I am in it... " (282) Although hardly able to see through his donkey mask and blinded by tears of rage and humiliation, elevated amidst the frantic masses, he still spots Bluebell in the gaudy tumult below and at long last comprehends—"he knows her now [ . . . ] for what she truly is: assassina!" (288) But he cannot move, and even if he could, she has again disappeared and left him behind. Solely through the combined help of the lion and the marionettes is he able to make it to his final meeting with the Fairy. Il più ultimo lazzo di Coover—A Malicious Joke: In this, his last chapter, Coover, topping everything gone on before with a final colpo di scena, brings together elements so drastically divergent as primal subconscious longings, blasphemic slapstick, archaic myth, folk tradition, utter nonsense, death struggle, comic-book episodes, and savage humor in one climactic scene. Titled "Exit"—another reference to theater and acting, to its artistry and artificiality as well as to its temporal limitations—the chapter ends with Pinenut's turning back into wood and his wish to become a book, the book the reader is holding in her hands. The circle closes. For that scene, Coover even finds the appropriately-named place in Pietro Lombardo's Church of Miracles and its sole painting by Niccolo di Pietro. As if made for Coover's purposes, its 1409 Madonna holds an infant Jesus who indeed looks like a cartoon character, and thus there is no holding back for Coover's malice and penchant for play. The final act is told in straightforward narrative—no flashbacks here—setting it off from all the preceding chapters. Now the Fairy shows her real face, which is to say, her many succuba-like impersonations throughout the ex-puppet's life appear like layers of a montage, more than a dozen of them: the Bella Bambina, his mamma, the blue-haired goat, a couple of Hollywood starlets, a colleague at university, several students, an interviewer, a doctor, a museum curator, a traveling companion to Stockholm, and Bluebell. Those fleeting traces of the familiar are now blurred by the strange. Claws on her fingertips. An iron tooth. Smoke curling out her nose, which seems to change shape with every breath. He has seen a scar grow, cross her brow, and rip vividly down her cheek and throat, then as quickly fade and vanish. A moment ago, her ears, peeking out from under hair twisting like thin blue snakes, seemed to be pointed [...]. An eye slips out of a socket, she pushes it back. Or perhaps the socket moves to cup the errant eye. (323) What he sees up there is [... ] a monstrous being, [... ] glimpses of tusk and claw and fiery eye. She is grotesque. Hideous. Beautiful. (329)Coover is definitely on home ground when peeling off face after face from virgin-mother, magician, witch, sorceress, prophetess, dragon, ogress, lover, and mother in one person. At last he reveals how very unfairy-like Mamma really is. The Blue-Haired Fairy displays traits of Astarte, the Semitic female god-figure, the Canaanite spouse of Baal: Anat, the Phrygian Cybele, the Egyptian goddesses Nut and her descendant Isis, the Greek monster Gorgo, the arch-sorceress Hekate, whose powers reach their culmination around midnight, Helios' daughter Circe, who entices with music and song, and his granddaughter Medea with her magic powers, Jocasta, who married her own son, Medusa with snake hair, but most of all the Sumerian-Babylonian female demon Lilith/Lilitu, who seduces and kills unsuspecting men and boys, the child slayer who murders her own children, who only becomes active at night when she forces men to copulate with her, who in Hebrew myth was the woman before Eve next to Adam, whom she fled when he refused to accept her as his (sexual) equal. Lilith/Lilitu also has a few positive characteristics, and the combination of those with her negative traits makes her the paradoxical yet archetypal "image within the human psyche of the mother— and, more generally, of woman—as destroyer" (Erich Neumann, Die grosse Mutter, 1956) With her, Coover goes back all the way to the very beginning of mankind, to the Terrible Mother as embodied in Uroboros (the snake biting its own tail and thus begetting itself), the Great Mother goddess who gives life and takes it away again. The figure of this First Mother symbolizes the full cycle of human existence: she is at once womb and grave. She personifies the uroboros stage, man's initial stage of awareness of the Ur-parent as incorporating both male and female, initial chaos and totality. With and around her the ego's fight with the dragon takes place, its struggle with paradoxes, opposites and contradicting principles in the process of individuation: a topos in all mythologies. But this being a Coover novel, such mythologizing and psychologizing is necessarily upended and ridiculed. Dogma-smasher Coover presents a variation all his own, a variation of the uroboros-incest theme. In his version the symbolic form of surrendering the self for a return to the prenatal stage takes a novel turn. It becomes a meditation on language, writing, and fiction-making. The process of representation is questioned in the course of the novel, is personified through Pinenut's numerous attempts at adequately representing himself—all of them futile. With "wood brought to life," or "she changed the wood to flesh" (92), or "And The Wood Was Made Flesh and Dwelt among Us" (281), Coover cunningly plays off against each other several intricate plot parallels. For example, Pinenut explains to his canine friend: "I am a household word. I am the ornament of metaphors, the pith of aphorisms, what's liked in similes—in some languages, Alidoro, a very verb!" (68) Later, the old professor says to him: "There are approximations, metaphors, allusions—but nothing close to the real thing." (91) Although all representations fail to render a particular experience, at the same time they are elaborate and enrich the meaning of experience. Or, to close with one of Pinenut's ruminations when he observes the snow dusting Venice: "Like a crisp clean sheet of paper, he thinks, and he is struck at the same time by the poignancy of the metaphor from the old days. For paper is no longer a debased surrogate for the stone tablets of old upon which one hammered out imperishable truths, but rather a ceaseless flow, fluttering through the printer like time itself, a medium for truth's restless fluidity, as flesh is for the spirit, and endlessly recyclable." (31)

Coover, Robert. Pinocchio in Venice. New York: Linden Press / Simon & Schuster, 1991. Coover, Robert. "Tale, Myth, Writer." Brothers & Beasts: An Anthology of Men on Fairy Tales, Kate Bernheimer (ed.), Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2007, 57-60. Coover, Robert. "Tale, Myth, Writer." Draft. Hudson, Gabe. "Notes on Craft: Some Instructions for Readers and Writers of American Fiction. An Interview with Robert Coover." McSweeney's, June 22, 2004.

Elisabeth Ly Bell, German-born Visiting Scholar at Brown University's Literary Arts Program, with an M.A. in American Studies from the University of Texas at Austin and a Ph.D. from the John F. Kennedy Institute for North American Studies at the Free University of Berlin, Germany. Her primary interest is in contemporary American fiction, and her teaching includes creation myths, fairy tales, and topics in American culture. Her scholarship on Coover has been published in Delta, Critique, and Review of Contemporary Fiction; she has also reviewed Coover's works for The Brown Community Bulletin and American Book Review and was interviewed on transferring literature to film in George Street Journal.

|