|

Eric Rosenbloom

In From the Beast to the

Blonde, Marina Warner explores fairy tales as tales told by the

silenced, the servants and nursemaids, the stepdaughter reduced to servitude

in her father's house. In Joyce's Ulysses, Stephen sees the “cracked

lookingglass of a servant” as a symbol of Irish art: Ireland, once

the land of saints and sages, is forced to wear the mantle of its English

conqueror.

Then the Hundred Years War

ended England's ties to France, and the ruling class started to use

the tongue of their subjects, filling it, however, with the vocabulary

of their own. Thus English became uniquely dual in nature: a simplified

Germanic grammar with a mixed Anglo-Saxon and French vocabulary.

And dual nature (“doublin

their mumper all the time” -- FW, p. 3) is what Finnegans

Wake is all about, in both theme and method.

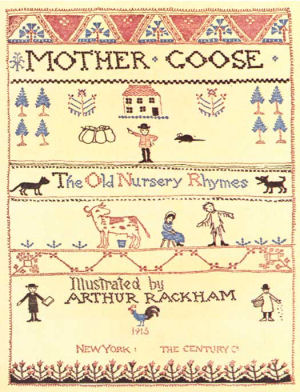

In another matter of dual natures,

Marina Warner connects Mother Goose with the sibyls, the wise women

of ancient Greece. In medieval Europe, the Sibyl was associated with

the Queen of Sheba (partly by the similarity in name) as well as with

the Sirene and Venus (as in Wagner's Tannhäuser). Aphrodite,

the Greek Venus, was sometimes said to ride on a goose. Thus the wisdom

of these women was popularly devolved to mere sex (though still a dark

mystery, at least as far as civilized man's relation to it, necessary,

sacred, and bestial). Their tales became the cackling of gossip -- women's

talk during women's work.

But raising children was also

women's work, and a certain wisdom or view of life continued to be taught

-- through nursery rhymes and fairy tales.

What is thus hidden, what deformities

of spirit that must be cloaked in nonsense and fantasy?

Her long slender bare legs

were delicate as a crane's and pure save where an emerald trail of seaweed

had fashioned itself as a sign upon the flesh. ... Her slate blue skirts

were kilted boldly about her waist and dovetailed behind her. ... The

first faint noise of gently moving water broke the silence, low and

faint and whispering, faint as the bells of sleep; hither and thither,

hither and thither ... (Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man,

James Joyce)

Tight boots? No. She's lame!

O! (Ulysses)

I do drench my jolly soul on

the pu pure beauty of hers past. In Arab tales of Solomon and

the Queen of Sheba (“solomn one and shebby, cod and coney” --

FW, p. 577), Solomon creates a river of glass in his palace, so

that Bilqis, as she is named, would raise her skirts to walk across

and thus reveal the truth of reports that she had an ass's foot, which

became a goose's foot as the story was retold in Europe (pes anserinus

instead of pes asininus). She does not, but the belief that she

did is defended by asserting that her foot was fixed, cured, purified

upon her accepting Solomon's religion.

Freud explained foot fetishism

as about what the foot supports, namely, the road to the secret cave

of the Sibyl, her genitalia. Thus in Finnegans Wake, Joyce finds

pairs of shoes on the beach on page 14 (“swart goody quickenshoon

and small illigant brogues” (like those left behind upon startling

a leprechaun at work (“she convorted him to the onesure allgood and

he became a luderman” (FW, p. 21; the Leprechaun is lucharman

in Ulster), “decent Lettrechaun” (FW, p. 419)) or Cinderella's

tiny glass slipper (originally French pantoufle en vair, squirrel

fur, not verre) after the dance). In the Irish telling of Cinderella,

“Fair, Brown, and Trembling”, which also includes a whale on the

beach, as on page 13 of Finnegans Wake, Trembling is dressed

(for church) by the henwife (see below). And Joyce draws a diagram/map

of ALP's bottom (“her sheba sheath”

-- FW, p. 198) on page 293 -- by circles with “a daintical

pair of accomplasses” (FW, p. 295). (Thus Shem becomes author

of himself as a sham ( German scham = vulva).)

Little Women, by Louisa

May Alcott, is, like Finnegans Wake, circular. The pattern is

a favorite of the self-conscious artist, who not only draws from her

own spiritual and emotional life for the matter of her tales, but also

knows that the teller is an intrinsic part of the tale, the creator

that is created by her own creation. The tale is about the creation

of the teller of the tale of the creation of the teller.

This is likely as true for

Finnegans Wake as it is for Portrait of the Artist as a Young

Man and Ulysses. Shem is merged into Shaun to become HCE

who merges with ALP ... that it may all start again, birth and death,

death and birth, the book of Lif.

The ass is typically masculine,

the goose feminine. When they talk, we are reminded of our animist past

(as in tales of hearing the speech of farm animals

-- and their secrets -- on Christmas Eve), when the hills and rivers

and trees were alive with spirits, spirits with which we were kin. And

so Finnegans Wake follows the Liffey river's circuitous route

(“riverrun” -- FW, p. 3) to the sea and to the hill of Howth.

The river is personified as ALP, which is German (whence much of Ireland's

fairy lore, via the Vikings) for mountain but also for elf,

and the latter also came to mean nightmare. When Germany became

Christian, names with Alp in them switched it to Engel (as Shaun dominates

the latter half of Finnegans Wake). Alp the incubus then, is

a demon only by reference to Christ (as the reverse might also be said).

She is in fact a voice still heard if only in sleep, free from the filters

of the day's demands and distractions -- thus is Finnegans Wake

a night book, its language reflecting the mingling of worlds, of the

people inside the hill (the shee) and the people who have built

atop the hill, of giants and elves and talking animals and quotidian

history.

One animal in particular appears

in Finnegans Wake to uncover what is hidden: “a cold fowl behaviourising

strangely on that fatal midden ... and what she was scratching at the

hour of klokking twelve looked for all this zogzag world like a goodishsized

sheet of letterpaper originating by transhipt from Boston (Mass.)”

(FW, pp. 110-111; the tale of “Fair, Brown, and Trembling”

was published in Boston); “henservants” (FW, p. 432); “henwives” (FW, p. 128). We may view the hen as a stand-in for Mother Goose, and thus for the Sirene, the Sibyl, and the Queen of Sheba, because she is an actor for ALP, the

hill-elf who may be said to be telling her story (or inspiring it to

be told). It is her letter that Shem copies and Shaun delivers (“you

will now parably receive, care of one of Mooseyeare Gooness's registered

andouterthus barrels” -- FW, p. 414; note that in Messr. Guinness

(brewer) here, Mooseyeare evokes ass as Gooness evokes

goose), and it is her voice speaking at

the end of the book. Coincidentally, the Greek for goose is

÷h´íá, pronounced hinna. And hana in Arabic means bliss; it is

also Old English for cock. Hen in German is henne.

The hen is also a manifestation

of Brighid, the mother goddess of old Ireland who was christianized

to St. Bridget. She was also known as Bride and Brid, which is a variant

of bird that was common in Old and Middle English. But the centrality

of Brighid in Finnegans Wake, particularly the rape of her abbess

on “31 Jan. 1132 a.d.” (FW, p. 420), is another story, already

told elsewhere by the late Clarence Sterling, although it is very much

a part of this one. And vice versa. (It should also be noted that Brighid

was a brewer -- see Mooseyeare Gooness, above.)

I sate me and settled with

the little crither of my hearth ... (FW, 549; Irish crith,

pronounced cree = tremble, i.e., Cinderella) Or all of these are avatars

of the one “bird” closest to Joyce: his partner Nora Barnacle, from

Galway in the west (like Grace O'Malley, a source for the Prankquean

of pages 21-23), whose name is also that of a goose well known to parts

of Ireland (particularly the west) and thought to grow in the sea from

driftwood or barnacles.

Ah ess, dapple ass! He will

be longing after the Grogram Grays. (FW, p. 609)

She. Shoe. Shone. (FW,

p. 441)

References

Jeremiah

Curtin, Myths and Folk-Lore of Ireland, 1890, Little, Brown &

Co., Boston.

Thomas Keightley, The

Fairy Mythology, 1878, G. Bell, London.

T. R. Lounsbury, History

of the English Language, 1879, Henry Holt & Co., New York.

Eric Rosenbloom, “The

Ravisht Bride”. In: A Word in Your Ear, 2005, Booksurge. Available

at:

http://www.rosenlake.net/fw/ Marina Warner, From

the Beast to the Blonde, 1994, Chatto & Windus, London.

|