|

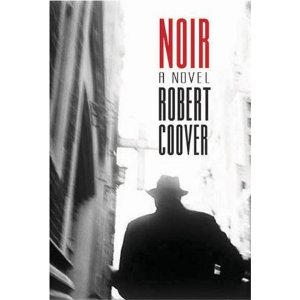

The city of Robert Coover's Noir is like most cities, not those figured and experienced in a good many fictions, but the ones inhabited in real life by individuals new to them or even those who have lived for a time within them. You know the place, or following a map you seem to discover it, the logic of its streets and parks, its newly come upon byways, the system of its underground transits. But then, as with "Someone you spotted out of the corner of your eye when distracted with something or someone else, but who wasn't there when you were able to turn and look, nothing left but maybe a trace of his sweet cigar smoke," [Noir, 92] the city suggests one of its many anomalies, not present on the map or in memory, and you are -- temporarily if you're lucky -- lost. If a reader does get lost in Noir it's for lack of attentiveness. Or else it's the way one gets lost walking the tortured byways of unfamiliar city streets, those not figured accurately on the map -- which is the memory, those expectations, but is not the territory. That is, it's like reading about something, trying to keep up, or living toward something, the as yet unknown, which is the future. In Noir, the past, that memory, and the present are often, crucially, conflated. Evidence of the chalked outline of the corpse's final gestures constantly changes, not only as physical tableau, but tonally. What seems appropriately somber, becomes comic, then crudely sexual. One might weep, but for laughing, much as the core idyll of the client's life story turns, in the retelling from romance to the comically lurid, questioning any sweet satisfaction Philip Noir or the reader might expect from it. "Out of the corner of your eye you see him trying on the bride's gown," [133] or we see Noir trying on those "pink silk panties with little flowers stitched on them" [47] belonging to his indomitable secretary Blanche. "The glossy silk felt good but they were a tight fit and some of your unmentionables hung out. She tried to help you push them in, and she could get one side in, but when she tried to push the other side in, the first one popped out. The whole exercise was making you lightheaded." [47] This is not out of the corner of the eye, but head on, yet like the mysterious details of the city (of the crime, the criminals and the victim, in short, "the story"), significance of the unmentionables cannot be successfully hidden or contained, though events and characters constantly attempt to do so. The chalk outline of the corpse, once the corpse is absent, is a map, a description of a perimeter, a surface, but the corpse itself is more like a city, this city, in that discovery of the cause of death (first step in unraveling the mystery of the crime) is gained through autopsy, which proceeds from the understanding that significance of surface comes from an examination of what's below it. The city is itself the story, and it has a bellyache. "Here's a principle: The body is always sick. Even when it's well, or thinks it is. Cells are eating cells. It's all about digestion. Or indigestion. What in the city we call corruption....Cities laid out on grids? The grid's just an overlay." [42] And the corpse in evidence of another crime? Below the benign surface: "His body was gutted by a friendly mortician with a habit and stuffed with bags of angel dust...and sewn up again, the brain cavity and scrotum filled with diamonds and emeralds from a recent heist." [55] Yet another autopsy would reveal this: truth (of a crime) in the underground. Curious how Coover continues to work this. Now it's the basement of a women's dress shop, and manikins. "In the dusty penumbral light, there's an eerie sensuality about them with their angular provocative poses, their hard glossy surfaces, their somnambulant masklike faces, features frozen in glacial eyeless gazes. In short, not unlike most of the women you've known." [116] In short, not unlike corpses, though only on the surface. And there is nothing but surface here. As Philip Noir sets forth to unearth the particulars of the crime and its attendant revelations -- appearance and disappearance of key characters, transformation of the seemingly know into the unknown, seduction and betrayal -- he finds himself quite often underground or at least confounded by avenues conforming to no expectations or mappings. In pursuit, he loses sight of his quarry as conventional pacing gives way to unreason. A fat man in a panama hat: "Finally, he was running flat out, pivoting sharply around corners like a mechanical carnival target on ball bearings, hopping nimbly over obstacles, darting down narrow passageways, somehow skirting puddles that you splashed through, a pale luminosity flitting through the moist shadowy alley like a will-o'-the wisp, and soon you were only catching fleeting glimpses of him in the distance and then you lost him altogether." [70] Just as we lose the story over and over and are put to the task of finding, reconstructing, or imagining it. "I have found, Mr. Noir, that if you make a story with gaps in it, people just step in to fill them up, they can't help themselves." [188] Words from the client herself, she who began all this. Yet at times Noir becomes startlingly, even beautifully conventional in the way it articulates atmospheres that parallel and enlighten the feel of works by some of the masters of the genre (Chandler, Hammett, Cain). "You'd been trailing along and no longer knew where you were. Didn't matter. Though you wished you'd remembered to pack heat, you were at home nowhere and anywhere. And there was something about these dark nameless streets going nowhere that resonated with your inner being. The desolation. The bitterness. The repugnant underbelly of existence." [41] The logical surface and the confusion below it, which may be thought of as yet another surface when it is treated as evidence, as it is here or in any detective novel. Evidence becomes a narrative, and Philip Noir, like Philip Marlowe, finds himself "meditating morosely on the thready web of story...[he's] become entangled in...." [146] Near the beginning of the novel, following shortly after Noir's client tells the romantic tale of those events that have brought her to the detective's office, another story, that of the prostitute Michiko, that now "suffocatingly perfumed bag of old painted bones" [22] is related. Michiko "while she was still just a kid in schoolgirl clothes...had been the moll of a notorious yakuza gangster who had his own portrait tattooed on the inside of her tender young thighs. Where he could keep an eye on things, he said." [22] Michiko was kidnapped by a rival gang leader, who "'blinded' the portrait with red splotches, and just for good measure added a mustache and blacked out two of the teeth before returning her to her lover. He also had his own hand, recognizable by its don't-fuck-with-me dragon tattoo on the back and the superhero code ring on his pinkie, tattooed over her plucked pubes, the middle finger disappearing between her lips." [22] Thus begins a series of tattoos and defacements, comic insults, intricate and imaginative extrapolations, until Machiko's body is completely covered with an intricate and constantly altered narrative, a battle between rivals that in the end becomes something quite different from what it started out to be. Thus, she continued to get passed back and forth between the two yakuza bosses as a kind of message board, the gangsters coming to so admire each other's art in the end that their rivalry, to the disgust of all their gang members, became purely an artistic epistolary one. They covered her with fragments of famous scenic and erotic masterpieces, always with implicit or explicit threats and insults, burned the signs of the zodiac in the appropriate places on her body, inscribed four centuries of yakuza history in all the blank spaces, covering even the soles of her feet, her lips and scalp, her eyelids and armpits. So obsessed were they, they might have started working on her insides had not their own lieutenants organized a public exhibit of Michiko in the city's modern art museum and, at the moment that they bowed to one another, executed both of them with tattoo needles fired into their ears. Michiko meanwhile ended up tattooed from crown to toes with layers of exotic overwritten graffiti, a veritable yakuza textbook, slang dictionary, and art gallery....All of it faded now. Losing its contours, its clarity, the colors muddying, wrinkles disturbing the continuities, obscuring the details. Suffering the fate of all history, which is only corruptible memory. Time passes, nothing stays the same; a sad thing. A haiku somewhere on her body says as much. [24-25] Defacement becomes adornment. Michiko's tattoos, proceeding from wit and then enacting a kind of (artistic) ritual, become a mask and Michiko the spirit behind the mask, dignified and protected by it. At least temporarily, until, as with all things, history claims her. The ritual of the tattooing could have gone on forever, the only limit the surface of Michiko's body, which in the tattooing terms as articulated by Coover is limitless. As is the city, both surface and underground, as it develops in Philip Noir's twisted, ongoing discoveries of it: "You can't see it and then, what do you know, you're in it." [69] In Noir, as with every one of Robert Coover's books, there is a need to read each sentence carefully, to stay with it as it were, rather than getting ahead or going back because of accelerations due to plot or psychological concern that might slow the reading, turning sentences in on themselves into a mire of heavy footed muddiness. The result of careful attention is that there is no future in Coover's writing, until the reader arrives at one, and there is no ending but for the artifice of empty space following the last words. Reading Coover, I sometimes remember how it feels to read other great writers, Dickens for example, how his cities are there after the first few paragraphs or pages, how once the reader is in those cities most anything at all can happen -- no endings, no beginnings, no future -- the city as a living entity in which Dickens and his readers are moving, an endless city. And this is true of Coover's novels as well. The mystery that confronts Philip Noir could have a multitude of possible unveilings, and this is very much like life. In this sense Robert Coover is the most realistic of novelists, so long as realism is taken as it might refer to living as opposed to literature. As Noir says, "It's funny. While you're working on a case, every outcome seems possible. When it's over, it's like nothing could have happened otherwise." [192] A case, or even a life. The future and the past. Note: The bracketed numbers come from the 2010 Overlook Duckworth edition of Noir: "Out of the Corner of the Eye" appears in the Robert Coover Festschrift of The Review of Contemporary Fiction, Spring 2012, Vol. XXXII, and is reprinted with permission.Overlook Duckworth Another review of NOIR can be found at FlashPøint #13.

Toby Olson's most recent novel is Tampico. His other novels include Life of Jesus, Seaview, The Woman Who Escaped From Shame, The Blond Box, and The Bitter Half.  |