|

Going Up To Sun Terrace by Li Bai An Explication, Translation & History

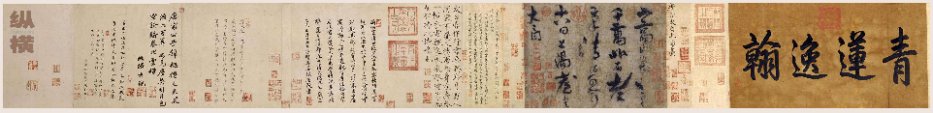

The calligraphy of Li Bai [Li Po], 701-762 AD, came as a great and delightful surprise. A real embarrassment of riches. I called my literary partner to come to the computer and said take a look at what Rosalie had put at the beginning of my set of poems. My wonderful partner�s first remark was �Wow! That�s nice calligraphy!� Then she looked closer and said, �Wait a minute, this line of characters on the side says it�s by Li Bai! Let me sit down there and look at it.� Our jaws had dropped�we had never even heard of such a thing existing. Further perusal found the seals of emperors which certainly lent authenticity to the scroll. And I took this with some embarrassment: that�s some mighty fine calligraphy for those little poems even though there�s a Li Bai line right there in the first poem. We vowed to do some research on this. I called FlashPoint editor Rosalie Gancie and coyly asked how come she had chosen that particular piece of calligraphy for art work for the set of poems. She said she came across it and just liked the look of it. That�s certainly a great example of original unsullied good taste�the eye looking first. Aesthetic perception unclouded by preconditioned reputation. The kind of thing one wishes could happen to oneself at least once in one�s life to assure one of one�s purely aesthetic values.

Li Bai has long had a reputation as a good calligrapher but that has been traditionally based on what others have said�the piece of calligraphy Rosalie Gancie came across is the only extant piece of Li Bai�s calligraphy known. And it has never�until now�been widely displayed or even very widely known of. It is now housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing. Scholars commonly acknowledge it as authentic and the only known surviving piece of calligraphy by Li Bai. The style of the calligraphy is �running hand� and it is not on silk but on traditional calligraphy paper. It is 38.1 cm by 28.5 cm. There are 25 characters in 5 lines. This consists of a poem of 4 lines of 4 characters each. The additional characters say �the eighteenth day [no month given] going up to Yang Tai [Temple] written [by] Li Bai.� Yang Tai (Sun Terrace) Temple was a Daoist temple where Li Bai went on an excursion with Du Fu [Tu Fu] and Gao Shi [Kao Shih]. Sun Terrace Temple still exists. It is on Wang Wu Mountain in the Jiyuan district of Henan Province. Wang Wu Mountain has a lot of caves and a long association with Daoist practitioners.

The poem was written in 744 the year Li Bai was banished from the imperial court (and the year he and Du Fu, eleven years younger, met). The poem is in an old poetic form which is called the Four Word Poem. This was the most popular poetic form of the Chou Dynasty and a good number of the poems of the classic Book of Songs are written in this form. So Li Bai was reaching way back, a thousand years or so, for this poetic form.

the ten thousand solid things,

Even with a fine old brush�

how could all this clear and strong�

This piece of calligraphy has passed through the hands of well known art collectors through the centuries including several emperors. When the last emperor was removed from the Forbidden City, it was offered for sale by an unknown source (most likely a high ranking eunuch with access to the imperial collection in the Forbidden City). It was purchased by a young art connoisseur named Zhang Boju. It stayed in his collection until the 1950s when he personally presented it to Mao as the most outstanding piece of art in his collection. He then donated the rest of his collection to the National Palace Museum. In 1958, Mao handed it over to the National Palace Museum.

The actual piece of calligraphy paper on which Li Bai wrote his poem is attached to a longer scroll which has been added to over the centuries as various scholars and connoisseurs have commented on the calligraphy, often in very good calligraphy themselves. Following are a few of those comments. The scroll begins from the right with four large characters by the Qian Long emperor (Qing Dynasty) which say, �Green Lotus�s extraordinary calligraphy.� �Green Lotus� was a name Li Bai gave himself. Further along, the Song Dynasty emperor Hui Zong, who is a very good calligrapher himself, and is famous for creating a thin elegant style of writing characters which characterizes his style. Hui Zong is commenting on a piece of Li Bai�s calligraphy which he apparently saw (he does not say directly that he saw it) and which is now lost. The emperor quotes the words of Li Bai�s calligraphy.

Hui Zong: �Li Bo wrote in running style:

Further along the scroll the Yuan scholar, Zhang Yan, wrote: � Li Po used to say that Ou, Yu, Chu, and Lu [all famous calligraphers] were really slaves to the art of calligraphy. Li Po saw his own calligraphy as flowing from his heart, unlike the calligraphy of those which can be accomplished by diligent practice. One can see his calligraphy flowing, as if riding on clouds. It�s wonders are way beyond the realm of this mundane world. I have studied the calligraphy of various greats of the Jin and Tang dynasties and yet when I came to view Li Po�s Going Up To Sun Terrace, I felt refreshed and renewed by it.�

The Yuan Dynasty calligrapher Ouyang Xuan, who was an excellent calligrapher himself and famous for it, wrote a poem after viewing Li Po�s �Going Up To Sun Terrace� calligraphy.

|

The whole scroll can be viewed at http://bbs.8mhh.com/thread-34372-1-3.html Scroll down to the long horizontal scroll:

Li Bai's calligraphy can also be found at: http://www.chinapage.com/calligraphy/libai111.html as part of Calligraphy of the Masters