|

|

|

Mary Ellen Bute Editor's Notes:

We're delighted to be able to add to the current online histories of Mary Ellen Bute by dedicating a section of this issue to her film Passages from Finnegans Wake. Kit Smyth Basquin's Introduction to a Screening of the film not only offers a personal glimpse into Bute's history but recounts the aesthetic choices she made as an artist in her rendering of Joyce's great work. Bute was absolutely a pioneer in the field of abstract animation. And in her quest for what could be called a new, 'mechanical' paintbrush she was able to work with some of the most celebrated innovators of her times. Her associations with these inventors and color & music theorists helped shape her own aesthetic path, which in turn helped her shape theirs. With these notes we hope to provide a little background information on some of her colleagues and direct the reader to additional sources about their achievements. "These

experiments by both musicians and

painters, men of wide experience

with their primary art material, have pushed this means of combining the two mediums up into our consciousness. This new medium of expression is the Absolute Film. Here the artist creates a world of color, form, movement and sound in which the elements are in a state of controllable flux, the two materials (visual and aural) being subject to any conceivable interrelation and modification." --

Mary Ellen Bute

Light * Form * Movement *Sound Originally published in Design Magazine, 1956. Online from the Center for Visual Music Library www.centerforvisualmusic.org

|

| It is in many ways fitting that the abstract

film pioneer Mary Ellen Bute would be the first person

to produce a selection from James Joyce's Finnegans

Wake on film.

Joyce himself was a fan of cinema. There are

many references to film in his works (too numerous

to mention here--a quick internet search will yield

enough to confirm the point). |

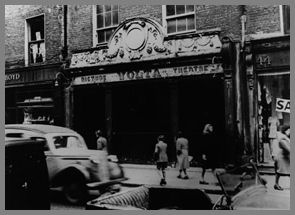

| And Joyce himself was for a short time the manager of a Dublin cinema, the Volta Cinematograph. While living in Trieste he contracted with some local businessmen to open a cinema in Dublin. In 1909 he opened the Volta Cinematograph, an event that was heralded in the The Evening Telegraph on December 21, 1909: |  45 Mary Street, Dublin in 1948 |

"Yesterday at 45 Mary St. a most interesting cinematograph exhibition was opened before a large number of invited visitors. The hall in which the display takes place is most admirably equipped for the purpose, and has been admirably laid out�[1] For more information on Joyce and the Volta (an

association that lasted only a few months) see Luke

McKernan's Bioscope

Blog. He wonderfully provides a short history, a

few stills from the films shown at the Volta, and

comments on his visit to an exhibition in Trieste: �Trieste,

James

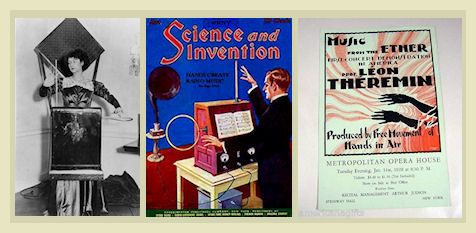

Joyce e il Cinema: Storia di Mondi Possibili�. Mary Ellen Bute came to film with a yearning to explore the abstract possiblities of visual art through many of the newer mechanical, and electronic, discoveries. According to Wheeler Dixon's The Exloding Eye: A Re-visionary History of the 1960's via Catrina Nieman, Bute was "frustrated by what she thought of as the "inflexibility" of painting--the confines of the frame, the flatness of the surface and, above all, its insistent muteness." [p.37] And from Bute herself: "There were so many things I wanted to say, stream-of-consciousness things, designs and patterns while listening to music. I felt I might be able to say [them] if I had an unending canvas." [Dixon, p.37]In the modernist tradition, her encounters with the visual art of Kandinsky, Klee, Braque & African Art attracted her to the possibility of animating the non-objective canvas. This desire to pursue the manipulation of light aesthetically initially led her to study stage lighting at Yale's new Drama School. The school was started in 1925 by George Pierce Baker, considered the country's leading playwrighting teacher, and Stanley McCandless, an architect and stage lighting designer. Bute was one of the first ten women admitted and studied there from 1925-26. Even here Bute was showing her ability to connect with those at the forefront of their profession. Both Baker and McCandless were proponents of what was called the 'New Stagecraft Movement', which held that all elements of a production, such as set design and lighting, were to be treated with equal merit as a means of conveying the artistic ethos of the play. Lighting & sets became dramatic elements of the play. Newer technical equipment such as electronic switchboards and electric stage lifts factored easily into this new approach. The school offered an exciting mix of technology and new ways of thinking about the presentation of theater. The university theater was new. Donald Oenslager, another emerging talent of the New Theater Movement, offered the first professional university course in scene design. McCandless, who had trained as an architect, began the first course on stage lighting. McCandless stayed close to his architectural roots and, in the modernist vein, made it a goal to merge architectural & lighting principles. This interest in the aesthetics of form & the mechanics of lighting led him to become one of the most influential people in the history of lighting design. Working in such an artistically charged atmosphere with state of the art equipment seems to have confirmed Bute's desire to find the right technological means of expressing her own artistic vision. Her continued pursuit of animating light & form led her to work with other innovators of the time who were merging art with technology. The online article, Reaching for Kinetic Art, recounts some of her comments from a 1976 talk at the Art Institute of Chicago: From Yale I got the job of taking drama around the world and got to see the Noh of Japan and the Taj Mahal of India, where gems surrounded the building. I looked into the gems and saw reflected the Taj Mahal and the lake and the whole thing appealed to me enormously. . . http://www.geocities.com/~barneyoldfield/HCBute.html

HARVARD INDEPENDENT FILM GROUP; reassembled from remarks at the Art Institute of Chicago, 1976, reprinted from Field of Vision Magazine, No 13, Spring 1985 |

|

|

|

|

"Light is the artist's sole

medium of expression. He must mold it by

optical means, almost as a sculptor models

clay. He must add colour, and finally motion

to his creation. Motion, the time dimension,

demands that he must be a choreographer in

space." "This art [Absolute

Film] is the interrelation of art, form, movement

and sound -- combined and selected to stimulate an aesthetic idea." -- from Light

* Form * Movement *Sound

Originally published in Design Magazine, 1956. Online from the Center for Visual Music Library Mary Ellen Bute Artist's Research Page www.centerforvisualmusic.org

|

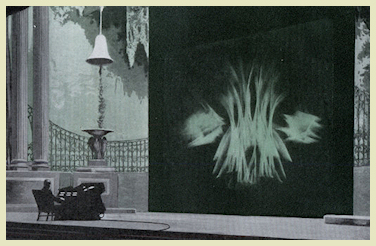

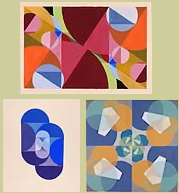

�Untitled,� Opus 161 |

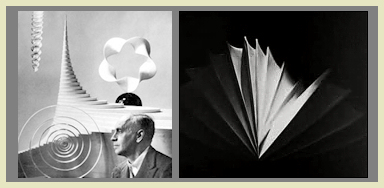

A 1925 Time magazine

review of a Clavilux concert described the 'metal

boxes' with a 'keyboard' that promptly surprised the

audience with its performance of light: "On the screen, like dyes filtered through

fathomless deep-sea canisters, colors fainted, burned,

swelled, darkened, dwindled, incredibly clear;

patterns crossed, shapes passed, cubes collided,

vortices spun down through hell, sucking the sight

with them, and the earth, like a small ball knitted by

music out of cloud and fire, whirled voiceless through

the gulf where sound and color merge." A Lumia show sample can be seen here: www.lumia-wilfred.org |

|

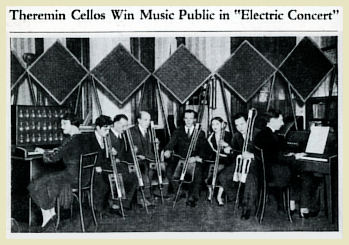

The

owner

of the townhouse which housed the studio would play

the instrument:

|