The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888) by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Magus Magnus

The Free Spirit Proposition

The “Free Spirit,” considered in its recurrent historical manifestation – as term and concept, as idea and ideal, and as elusive attainment in some singular instances – offers the possibility of radical liberation from societal constraint. Its history is admixed with the history of religion, since its attainment is connected to higher experience, and its liberties and license have often been given sanction by mysticism; indeed, the Brethren of the Free Spirit (later condemned as the Heresy of the Free Spirit, or Cult of the Free Spirit) was a lay Christian religious movement during the late Middle Ages. Beyond Cult or Heresy, with reference to its expressions both secular and spiritual in the realms of art, thought, and life, this radical liberation of the individual in connection with higher experience for me gives rise to the idea of a Canon of the Free Spirit – in this space I hope simply to give a suggestion of the possibility of this Canon: writings, philosophy, and life instances marked by freedom preserved or attained in spite of societal or existential hampering. Often such are marked by the ecstasy of the unleashed; here, the aesthetics of liberation have a relation to “the poetic,” which at a certain standard of definition combines thought and sense, feeling and language, and life-blood, into moments of cruel beauty – at least that’s the way Antonin Artaud would have it, as a mad Free Spirit and damned poet. The upward spiraling of spirit seeking liberation corresponds to the mystic interpretation of “To the pure all things are pure”: such can yield the licentiousness and charlatanism of figures like Rasputin and the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi, and yet even a saintly person like Marguerite Porete – author of The Mirror of Simple Souls – gets burned at the stake. When applied to secular life, notions of the Free Spirit devolve into mere lifestyle, as with the hippies and beat wannabes; yet, a living Free Spirit is the essence of inspiration – and remains rare and refreshing. In life beyond lifestyle, radical freedom associated with power has given us some of the worst tyrants ever; and yet, Akhnaton once ruled. Perhaps it is best manifested in freedom of thought, and lived thought/lived poetry: Blake, Artaud, Nietzsche, Heraclitus, as a start.

In fact, my start has been with the Ancient Greek philosopher Heraclitus, whom I’ll focus on here, along with ancient Roman emperor Heliogabalus: two extremely different and distinct figures, extreme personalities, and each in their own way exemplary of what I mean by the Free Spirit. I entered into their worlds at separate times and for separate projects, and out of the tension of “unapparent connections” (with reference to Heraclitus fragment 54 according to the Diels-Kranz ordering) between the two of them, came first inklings of a broader orientation to the Free Spirit proposition, from historic heresy to ahistoric ideal, from Cult to Canon.

Probably it’s absurd to suggest a Canon of the Free Spirit,

since so often assertions of authority prop up a canon

(just as canonical assertions prop up authority)

incongruous to anti-authoritarian independence and free-spiritedness

celebrated here;

and yet I’ve always believed in canons as reflective of an intrinsic lasting power

in certain worthy works

despite concurrent politicking (canon-building/canon-forcing),

and so I think there can be works and instances of the Free Spirit

that persist through history,

affirmations in themselves,

to be further affirmed in keeping with their self-affirmative nature.

Spirituality, Mysticism, and Monotheism

Allow me to course over history for a moment, as the Free Spirit itself courses over history, and cull from millennia some key associations connected with its emergence: Spirituality foremost, remembering that the term “Free Spirit” includes the word spirit, and keeps focus on it, as distinct from – though often related to – mental and intellectual freedom, political and economic emancipation; also, Mysticism, practices towards Union with God, which can be experienced as identification with God, with God’s will, along with perilous implications of such; and finally, Monotheism – although the Free Spirit has substantial qualities and pathways compatible with pantheism, and paganism, the Dionysian for sure, and other Mystery religions, I find it repeatedly and drastically associated with Monotheism.

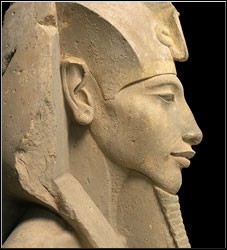

Akhnaton is a great instance of this.

Akhnaton [c.1351–1334 BCE, Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt]

The Egyptian pharaoh (14th century BCE) has been described as the first individual, the first romantic lover, and the first scientist, or, free thinker – this last due to his correct and corrective knowledge of the solar system developed in connection with the controversial imposition during his reign, in a proto-monotheistic manner, of his Sun God Aton. This sun worship type of monotheism prefigures what went on with Heliogabalus, as will be conveyed; Heraclitus, too, mentions the sun more than once. Notably, Freud’s Moses and Monotheism links Akhnaton’s reign and religion to the Judaic tradition. Akhanaton can’t be mentioned without his consort, Nefertiti, her beauty immortalized by the sculptor Thutmose. Her name means “the Beautiful one has come,” and her royal name in full, Neferneferuaton Nefertiti, means “Beautiful are the Beauties of Aton, the Beautiful one has come.” The Free Spirit heralds the first famous, real-life, beautiful couple, Akhnaton and Nefertiti, and brings love and the beauty of love into marriage – erotic beauty – and, with it, the possibility and actuality of true male-female partnership. Nefertiti ultimately stood equal to and alongside Akhnaton, and she inaugurates the strong feminine component evident throughout the history of the Free Spirit, woman as human and spiritual being.

Indeed, a woman is the central figure of the actual medieval Heresy of the Free Spirit, Marguerite Porete, of martyred intellectual integrity.

Marguerite Porete (by Hans Memling, c.1470)

The complete title of Porete’s book can be translated as The Mirror of Simple Souls Annihilated and Who Abide Only in Will and Desire of Love. Clear-sighted with the probity of her own soul, she distinguishes Seven Stages of Grace, and indicates a mystic process by which one’s own life, self, and will dissolve into divine love, until one wills only God’s will. A French bishop publically burned her book before her eyes, but she rewrote – and expanded – the work and continued to propagate her beliefs; before long, the Inquisition caught up with her, found her guilty of heresy (also declared her a pseudo-mulier for good measure, a “pseudo-woman” or “fake woman”), and in Paris on June 1st, 1310 CE torched her for her refusal to recant, cooperate, and confess. Aside from the challenge to ecclesiastical authority represented by any doctrine of direct access to the divine, Porete’s book in particular upholds some ideas intrinsically problematic whether or not in confrontation with powers-that-be: once at the stage of being one with God’s will, whatever one wills is God’s will, and anarchy enters the equation (what Artaud finds in Heliogabalus), mystical anarchism through human identification with God’s will. Of course, with Porete, Soul does as it pleases, in Love; and with Porete, of course, the love is pure. “…permission to do all that pleases him, by the witness of Love herself, who says to the Soul: My love, love and do what you will.” (Ellen Babinsky translation)

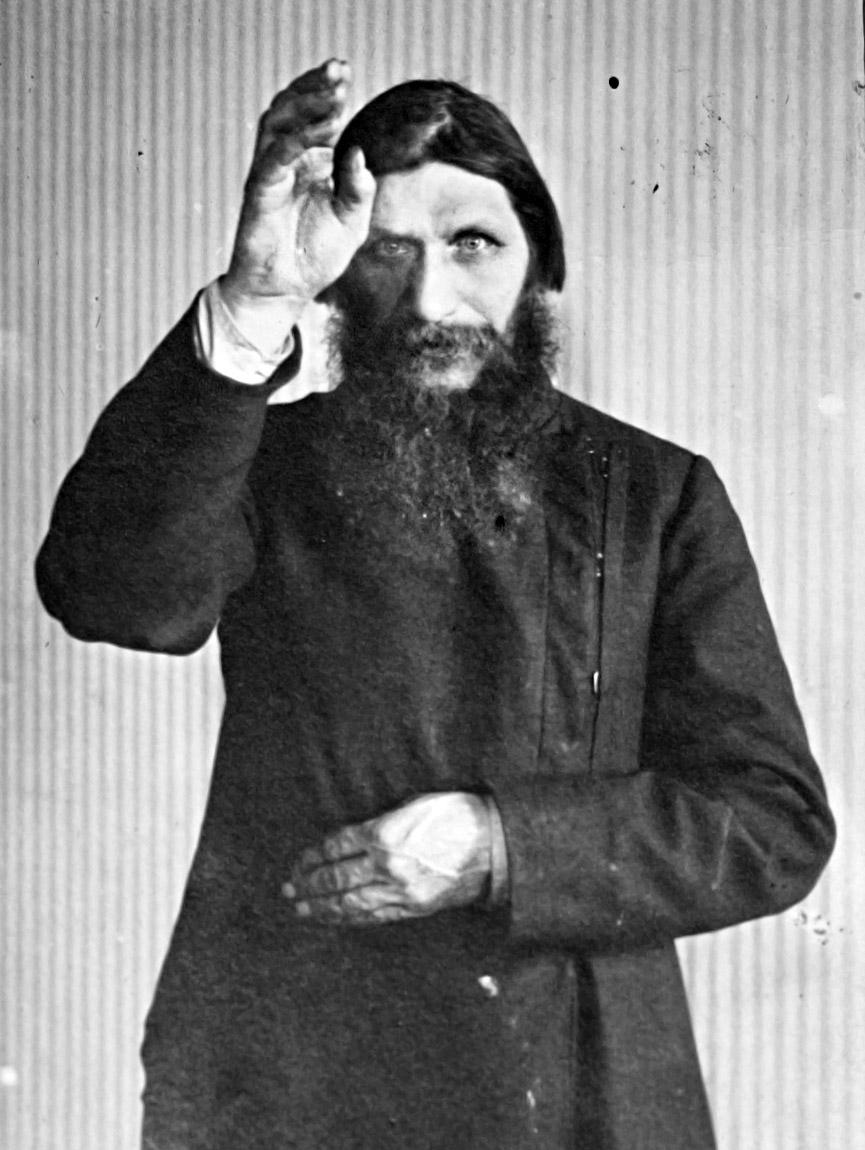

Just the sort of thing to justify Rasputin.

Grigori Yefimovich Rasputin (1869-1916)

Deeply intriguing along the line where true religious practice spills over into anarchic affirmation of volition, howsoever spontaneous, strategic, or self-serving it may be, Grigori Rasputin’s energy, charisma, and power seemed to have come out of the ecstatic binary of his well-documented oscillation between extreme licentiousness and extreme prayerful repentance. Here, as elsewhere with the Free Spirit, the ethical becomes an outside category. “Love has freed the Unencumbered Soul from the Law of the Virtues,” wrote Marguerite Porete, and although centuries and geography separate her from Rasputin’s Russian Orthodox context, her context of Christian millennialism corresponds to some of the teachings of the secretive Khlysty sect associated with Rasputin, its rumored ritualistic self-flagellation and orgies notwithstanding.

…with the Free Spirit, the ethical becomes an outside category

So, here are a few points of reference for now, that’s all: key figures, key associations, leaving on the table many possibilities, leaving open a potential comprehensive list for the reader to help populate according to her or his affinities, in alignment with this developing orientation towards a free – and never final – Canon. To be noted about the three figures touched upon above: each has been an attractive subject for art and literature, and yet we find no definitive masterworks on any. Heliogabalus, too, figures similarly. Strange treatments on Akhnaton include the joyous Son of the Sun by the severely compromised, questionable, and disturbing Savitri Devi, along with an unproduced play by Agatha Christie and a minor novel by Allen Drury; at least we have Anne Carson – in her Decreation, with an essay and accompanying libretto – upturning, overturning any easy instinct regarding the realness and “fakeness” of our absolute Marguerite Porete; and there has been as many or more artists making dramatic attempts on a Life of Rasputin as there had been enemies plotting attempts on his life. Are Free Spirits such as these too elusive, layered, and complicated in the paradox of their human-divine liberation to be decisively pinned down? In other words, are Free Spirits bigger and weirder than Art? A challenge to artists and writers everywhere, for all times.

This is my take on the Free Spirit. As in, “Those are my principles, and if you don’t like them… well, I have others.” – Groucho Marx

In proffering my own free-spirited take on the Free Spirit, I’ll gladly admit to departures from earlier instructive sources of my pursuit, interpretations inspirational even in divergence to how I now qualify the notion, and whom I qualify for it, impressionistic as such may remain.

Recommended Reading

for other orientations to the Free Spirit:

Norman Cohn’s The Pursuit of the Millenium

Greil Marcus’ Lipstick Traces

Hakim Bey’s T.A.Z.

It’d be understandable for purists to keep strict hold of the term in its historic sense, maintaining academic rigor, exacting correct usage through accurately and punctiliously sticking its understanding to the actual movement and heresy: all other uses of the Free Spirit are – too free! Nevertheless, Norman Cohn’s book will continue irrepressibly to excite and to fascinate with the revelations produced by its scholarship for decades to come, and The Mirror of Simple Souls itself, as unfathomable looking glass, will never cease – to the shock of any new receptive (or susceptible) reader - its unpredictable sudden shattering from the inside. C-crr-raaaaack!

As well, I can’t help appreciating the hooks of Lipstick Traces, deep history by way of music journalism, in which a safety pin in the cheek of punk fastens a dangly makeshift chain of fetishistic influences from the Situationist International and Lettrism, to Dada, and on back – as might be suspected by now – to the Brethren. The linkages are brutal, and certainly I discern a Dadaist “canon” (as contradictory in principle as the prospective one currently in question, albeit towards wholly other topics, poetics, and aesthetics), but as much as I love the Situationists, I don’t consider them Free Spirits. Maybe a few Dadaists were. As much as the personalities delineated by Greil Marcus were free thinkers and pranksters, they lacked the Grand Style of life, action, and personal stamp I’m finding essential to the designation. They weren’t bigger than Art, and for the most part there was smallness to their acts of subversion, deliberately so, since their commitment was to the field of endeavor of everyday life. Détournement, as a weapon of revolution, is a gun that merely drops out a flag that reads “Bang!” In short, they lacked Spirit (as would make sense for dedicated anti-authoritarian Marxist materialists). Yet, May ’68 wasn’t clowning, and it’s amazing a few theoreticians ignited widespread uprisings, factory and university occupations, and the first wildcat mass strike in history, involving greater than 22% of the French population.

In contrast, I wonder myself at the instinctive distinction-making here where I tend to include TAZ personalities and scenarios with the truly Free-Spirited (Hakim Bey, AKA Peter Lamborn Wilson, has his book title in full as: T.A.Z. The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism). Pirate Utopias, glorification of Gabriele D’Annunzio’s takeover and artistic dictatorship in Fiume – quick indicators of Free Spirit in the Grand Style. Maybe it’s because, despite the Autonomist cultural context and background TAZ shares with SI, the spiritual isn’t anathema here, and Bey feels free to employ terms like “sorcery,” “anarcho-mysticism,” and “revolutionary HooDoo” – also “radical aristocratism,” in frank moving away from an egalitarian ethos. (One of Heraclitus’ fundamental words: aristos, ἄριστος). There again the ethical gets left out when spirit revives its spiritedness, and claims the privileges of the untamed. Yet, forever, the Free Spirit is accessible to anybody; that is, no one is disqualified from it intrinsically, however unlikely or prohibitive a given social-economic situation might be to its attainment.

“Reason, you’ll always be half-blind.” – Marguerite Porete

Nietzsche, the Dionysian, Sartre

It’s impossible to mention the Grand Style, along with D’Annunzio as a first wave Nietzschean superman-poet, without turning to Friedrich Nietzsche himself for immersion in ecstatic insight – the Dionysian current. I don’t neglect the Apollinian when considering Nietzsche’s work as a whole, but to get at pagan elements of the Free Spirit – associations with Monotheism aside – I’ll pour libations to the leopard-riding god. Rites of Dionysius unleashed feminine frenzy, his female worshippers liberated by music, wine, and dance; bands of these women, known as Maenads, brought disorder to the countryside, ready to tear apart and eat raw any seeming temporary incarnation of their deity they happen to come across, whether animal or man. Euripides had them bare-handedly dismember King Pentheus, who got in the way of their faith; and it is said they similarly and orgiastically tore apart the founder of their own Mysteries – form-generator Orpheus – limb from limb. This is myth and imagery perhaps too violent for purposes of spiritual elevation, this “rapture of the Dionysian state with its annihilation of the ordinary bounds and limits of existence” as described by Nietzsche in The Birth of Tragedy, his first book. “…life is at the bottom of things, despite all the changes of appearances, indestructibly powerful and pleasurable” (both quotes translated by Walter Kaufmann). Not exactly heights, but chthonic depths – and “at the bottom of things,” Life! By the way, nothing here to oppose Heraclitean unity within Heraclitean flux. Human, All Too Human, an intermediate book of Nietzsche’s, carries the subtitle “A Book for Free Spirits,” and it’s necessary to keep in mind that for Nietzsche freedom is likewise an intermediate phase, to be superseded by the Will to Power (as drafted in his later thought). To put it more precisely, will to freedom is a guise of the Will to Power’s seeking escape from others’ power, escape from oppression; once secured as “freedom,” the will naturally moves on to seek its own power – over things, over circumstances, over others.

To the contrary, Jean-Paul Sartre treats human freedom as an end in itself, and an existential given. It is inescapable, and best be confronted as such. In the section “Why Write?” from his What is Literature?, Sartre suggests that we must as writers and thinkers generously address ourselves to human freedom for the sake of our own aspirations towards success and real excellence. Only through reliance on readers’ highest human capacity to respond – in freedom – to whatever’s written does the writer allow the writing to be truly realized in every sense, creative realization of the work being dependent on the reader; and only in that entrustment (generosity as the character of the relationship between writer and presumed reader), can an implicit reciprocal demand for the highest make itself manifest: an upward spiraling of the human spirit. Aesthetic joy emerges as a possibility from this profound and heightened respect for human freedom, since to understand and be understood at that depth and height is to meet and be met there, where the particular is universal; according to Sartre, there’s a sameness to understanding at the highest human capacity – for all of humanity is present in its highest freedom.

If this is so, might the problem of the externality of the ethical to Free Spirit sway be resolved through discernment, in that highest human freedom, of a universal imperative making itself particularly known? But the generosity required would have to be godlike.

“Improvement makes strait roads, but the crooked roads

without Improvement are roads of Genius.”

&!

“The soul of sweet delight can never be defil’d”

– William Blake

Heraclitus

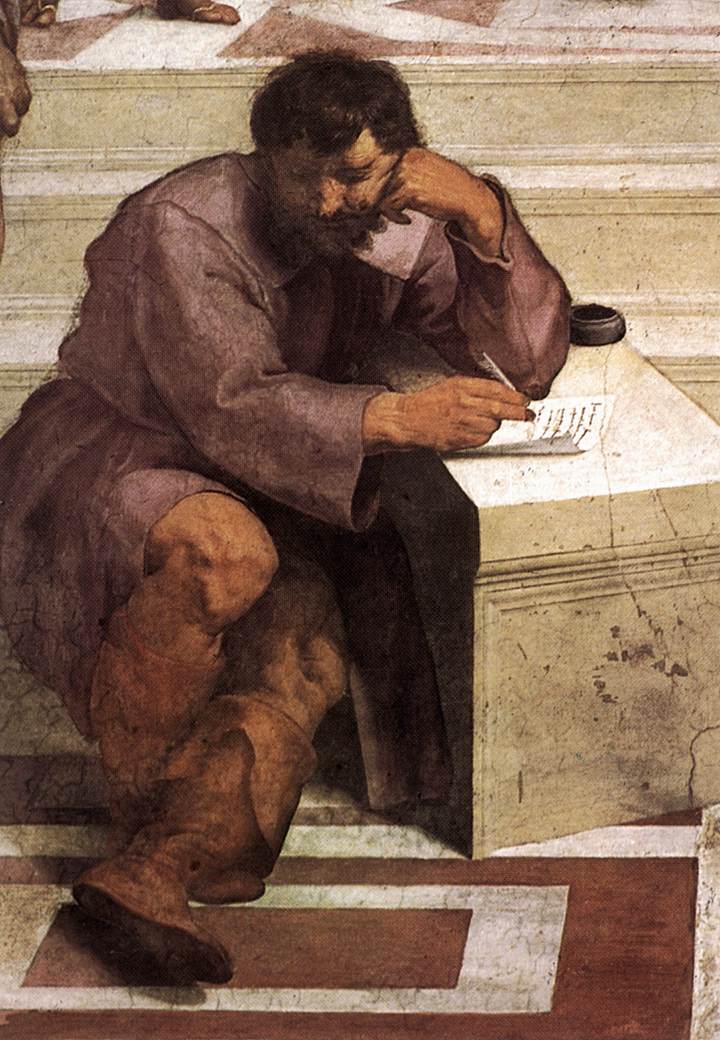

Detail from The School of Athens

Raphael chose Michelangelo as the model for Heraclitus in his fresco The School of Athens (1509-1510 CE), here in detail, and thus – intuitively, spiritually, ahistorically – bridged a gap of two millennia through Art: again, through the spirit, and against timid strictures of historicism, we can access people across the ages. Getting into the spirit of the men. Raphael chose brilliantly. Michelangelo and Heraclitus are well-matched temperamentally, red-blooded and robust as each of them were; however, I don’t really consider Michelangelo a Free Spirit the way I do Heraclitus. A terrible genius, yes – but probably not a Free Spirit. I don’t find in him a certain quality perceptible in the brooding philosopher’s sallying, surging manner of thought. I’ll have to re-read his sonnets after all these years, and discover in-person the resident energy of his paints, in Rome, to know for sure. I did enter ekphrastically into the immeasurable, his face as Raphael painted it, as part of my entering into the spirit of Heraclitus’ thinking for my book, Heraclitean Pride.

The Countenance of Heraclitus

His gaze, having once existed, coming out of time and the universe. A gleaming, streaming sublimity. Forever. His fire-gaze. He was a terrible man, in the best sense of the matter, and that yet and ever emanates from his face. Through the dark. In the best sense of the manner. Wrathful. Stern. Cast in light, plunged into shadow, blue shadows. A blazing star, impinged upon by nothingness and outer space. Streaked by the cool shades of swaying yard-high grass, a royal-maned lion. Fire and ferocity, each quality contrasted by shadow. Oblivion opposing him, vain vacuum. For he is, forevermore. Dark-eyed, flashing pride and suffering, anguish into anger. Thick-faced, hale, mighty. Meaty thick jaw, deep-lined features. Sun-seared, swart. Heavy dark-shadowed eyes, a bluish tinge to the dark circles under his eyes, midnight blue. Deep sunken eyes, glittering with sunken treasure beneath their depths, gemstones, gold, piles of coin spilt upon a vast silence of ocean floor. Had he lived between his time and this, perhaps he’d ’ve become a rover on the Spanish main, flying the Jolly Roger. Black and bone-white, light and dark, that image on a piece of torn bunting, so close to his own shivering venturesomely through historical interpretation and judgment still, above sails set against savage winds. Fierce, misted with spindrift, his face reflected upon the undulating blue-black waters. Philosophically piratical, his life of adventure and defiance in thought. Wind-blown, bushy brown hair. Curly-bearded. Sinewy, muscular, thick-necked. Weightily sleek, lithesome, full of bodily vigor, with teeth-gritting carnivorous naturalness. Leonine, but as in a very individual and outcast lion, hungry, harried, disgruntled, living off his Jungle King pride, cut off from the pride. Downcast though enduring, strong. Exuding strength, and red-earth fleshliness. Heavy, brooding, lowering at every approaching stranger. Broad-browed, yet with pinched features: scornful narrowing eyes, a wrinkled pointed nose. Glower and glow, for his thought. Deep in thought. Somber head-on-hand thoughtfulness. A statuesque head, bust-like with broad shoulders. His stony glare. Hard, heavy, yet an underlying poignancy of expression beautifully knifed and etched by his almost holy dedication. Nearly whole, his overcoming of adversity. But there’s something bitter about his smiling mouth, amusement’s there also, an unsympathetic laughing at the world, rufous cheeks cracked into a smile, a snigger. Such flesh-felt corporeal spirituality. Still, he’s sky-wide: bright skies, heavy skies, used to shining, used to thundering. Dropping thunderbolts with his truth-telling. Lightning in his eyes, flashes of his truth. His dignity, as of Greek Kings, natural and savage and divine. Grandeur of tragedy, catastrophe, yet exhibitive of an everlasting inward triumph. Really, reality at the core. Deep calm beneath a turbulent surface, sea-like. Sun-like raging flame and gentle radiance. A mask of gold, melting. His face an ice sculpture, a fire-pillar, a stretch of some red river that is never the same, different and different, indifferent to him and to his image which it distorts by its relentless flow. Alternately heated and freezing, face in flux, quick changes of temperature creating a brittle crystallization of that aspect. Whatever he is remains, though; a face and a fame, he remains awesome in inmost immovability, inextinguishable substance, fire-substance. Live austere beauty. Deadly serious. His look penetrating the ages with intelligence and seriousness, that there’s something to take seriously in life and existence. The Game. Beauty. Thought. His gaze, his glance: engulfing. Soul.

“One will never discover the limits of the soul,

even should one traverse every path –

so deep a measure does it possess.”

/

“…so deep a Logos does it possess.”

(Heraclitus fragment 45, D-K ordering)

Λόγος for “measure”

Heraclitean Pride treats fragment 86 in a manner apropos to Free Spirit aspirations and difficulties, with a passage giving the book its title:

Much of the divine escapes ascertainment because of lack of belief.A call to faith, maybe. To just believe, especially a just belief: divinity’s presence. To take the jump, that leap of such famous philosophical difficulty, problematic intellection, to understand without rationalization. To let oneself understand. Believing one’s own insight. But it could be otherwise interpreted.

Much of the divine escapes ascertainment because of lack of confidence.Confidence in the divine, it may be. A lack of confidence in the truth, or in the belief of that truth, or in its grounds, or even in its rationalization. Confidence itself; as in, lack of confidence in one’s own understanding. Lack of confidence in oneself. This too could be otherwise interpreted, more strongly.

Much of the divine escapes ascertainment because of lack of pride.

The word is άπιστίῃ, apistis

Through contemplation, and thinking one’s own thought: ascertainment, connection to the divine. A philosophical path taking one through stages similar to those of mystical Union with God, Identification with God’s will, to – is it Pride, or Hubris? – exalted states of human deification, ecstatic self-deification, which brings me to…

Heliogabalus, teenage pansexual Roman Emperor, high priest of Sol Invictus, the unconquerable Sun. My in-progress book to be titled: Heliogabalus, Priest of the Sun, Emperor of Rome.

The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888) by Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Sir Lawrence Alma-Tadema in his painting, The Roses of Heliogabalus (1888), depicts one of the most fantastical, absurd, sadistic, exquisite, cruel pranks ever ascribed to anyone. Interpretations of Heliogabalus’ decadence abound, and it’s true he’s a figure on par with Caligula and Nero for accusations of extreme licentiousness and out-of-control autarchy. Whether apocryphal or no, it’s crucial for integrity’s sake to true the revealing legends, and so Alma-Tadema had blossoms sent to him weekly from the Riviera during the months of his working on the painting – to get it right. Of like loving detail are the rose petals on the cover art of John Zorn’s album, Six Litanies for Heliogabalus, the soundtrack for my musings, which incorporates classical musical structures, serene medieval chanting, and punk rhythms with stylized screaming – three elements I consider applicable to my Heliogabalus book, and to my work in general: the classical, the truly religious or spiritual (for the medieval chanting), and as well contemporary artistic disruption, postpunk postmodern, postlangpo exuberance.

Roses of Heliogabalus

The emperor regales his guests. A feast in lounging fragrant luxury, savory morsels on the tip of every tongue – crushed overripe figs dripping over open mouths. Marble columns roll out a vista of white-streaked pale blue skies over a line of hills. Birdsong from the open air accompanies music and chatter inside the banquet hall; softly, as if from the sky, inside, rose petals begin to fall, float on the air above revelers’ heads.

A feast in languid luxury, half-draped lounging bodies, perfumed, on tasseled cushions – two or three mouths at once share the burst syrup and seedy red-purplish flesh of overripe figs. A savor of sizzling meats, in strips and slabs, greets the revelers. Floor and columns of exquisite marble, blue veins on creamy white. Twittering of starlings and finches from the open air reaches languorous female laughter inside, women with husky voices; next to the emperor stretched on his couch, a musician with puffed cheeks plays an ivory double flute. Up and out of the way of his guests, on a dais where the columns open out to white-streaked sky behind him, he watches as floating rose petals land on platters of delicacies, already sprinkled with gold dust, and into bowls of fruit, bowls of wine throughout the banquet hall before him, also onto people’s faces, headdresses, and eyelashes. Stretched on his stomach, with a few favorites female and male – feminine and effeminate respectively, each wearing silks, make-up, and simpers – sharing his high table, he caresses a pomegranate in both hands, heavy bracelets dangling from his wrists. The rose petals are of blush and cherry, some mostly white with just a tinge of pink, and they are coming down a handful at a time now, snowy clumps, and people start to notice, and look up at what’s falling around them. Sometimes just a tinge of pinkness on the white petals, as of certain sunrises or sunsets with peculiar infusions of color in paleness, lightest traces of colored light on the horizon. Titters and squeals of delight as revelers awaken to rose petals floating around them amidst the sumptuousness of the feast.

Revelers awaken to rose petals floating and falling around them amidst the sumptuousness of the feast. Some people lounging, some rising, they raise their arms to the petals swirling around them; half-clad – naked breasts, naked flanks and thighs – titters and squeals of delight – bodies dance amidst the petals, people are drinking and laughing, husky female voices. The banquet hall is awash in color. Rose petals are everywhere, filling the air, and the emperor and his favorites watch with amusement from their high table as guests dance, exultant, in and part of the flickering cascade of pinks and snowy whites, rose-pinks and blood reds, magenta, violet, and blush, showing their own flesh-pinks, olive and amber beneath flashing rose-dyed linens, and shiny silks of purple, citrine, and chartreuse. The emperor’s favorites feed from a mound of apples, citruses, pomegranates, and other fruit, while he rinses sticky juices from his fingers in a polished silver washstand next to his couch, never taking eyes off his exulting guests. Music from double flutes increases in tempo and shrillness as the rose petals fall faster, in clumps, and shadows pass over faces and bodies, quickly now, a darting – tinged light of the petals and then shadow of the petals – something sudden and unsettling, seen at the corner of the eye. Flitting by of shadows of swirling, clumping rose petals, like darting insects, flick of dragonflies.

The banquet hall is awash in color of rose petals. It is a thick snow, petals are everywhere, literally filling the air, saturating the space of the room in red and pink and pink-tinged white; and the once exulting revelers, covered by this fragrant blizzard, grow silent in accordance with the sound of silence of a thick snow – that extraordinary muting. Like a snow, the thickness of falling petals mutes everything inside the hall from the bottom up; the muting itself fills the room, slowly, beginning with the tamped sound of petals landing in feathery mass across the floor and cushions. Jerky movement of people amidst this increasing density of flickering hues in the room – sudden violent thrashing to sweep open some space – puffs out bursts of petals here and there in muffled, fluffy explosions. A huge sheet of sailcloth flaps from the ceiling, flapping out the rose petals; of slick canvas stained a creamy marigold, previously unnoticed, retractable with ropes and pulleys, this false ceiling had at first shook out a little at a time, then clumps, and now a full massive dump. Up and out of the way at his table, the emperor glances at the mechanics of the apparatus under the real marble ceiling of the banquet hall, and observes his guests’ predicament with amused expectation. As of wet lumpy snow, the petals come down, fresh and heavy flakes, and the soft weight of it all induces anyone still upright to rejoin those who had remained lounging; all must settle down into the padding, and into an eerie, too-easy silence – as into a great muffling blanket, cushiony, yet no comforter. There’s an uncanny audibility to the spreading hush. Everyone yields to the gentle but relentless pressure from above, cushioned in their giving way; they ease down into a shared bed and pillows of rose petals, layer upon rising layer.

The banquet hall is a shared bed of rose petals, layers rising upon layers in spreading hush. The emperor’s guests give way, fall or recline further, weighted down, as under a great muffling blanket. Yet now they break the silence coming over them, resist the gentle but relentless pressure from above, rebel against the uncannily pleasant muting: in growing panic, some begin to scream – try to scream – and violently attempt to fight off the ease at which they feel themselves succumbing to comfortably soft smothering. Sudden anguished desperate thrashing to sweep open some air: for now what the revelers delighted in is revealed to be utter and inescapable horror, torture. The screaming is piercing, yet each scream is inevitably cut short, destined to be short-lived and muffled, all wailing and shrieking choked on and broken down into coughs, sobs, and last gasps.

The emperor regales his guests. Softly, the last of the rose petals fall; the banquet hall’s false ceiling of canvas sailcloth flaps down in its full retraction, shakes out, empties the last of its load. The revelers can barely move now, weighted down in what formerly delighted them, as under a great suffocating blanket. They go silent again, unable to resist the gentle but relentless pressure; their screams are smothered in rose petals – mouths stuffed, throats choked, nostrils blocked, for torturous cloying luxurious perfumed muting. Still some effort, some climbing on top of each other is attempted, sluggishness of limb over limb, foot into face, useless, no way to dig out amidst mawkishness of a flowery grave, mockery of the sensuality and luxury in their festivities, tomb much of a good thing, heaps of rose petals over the feast.

Softly, as if from the sky, inside the banquet hall, a last rose petal falls, floats on air, flutters downward and turns over, twirls, until it lands on the great heap of rose petals covering the feast, like great drifts of – pinkish-white, and cherry red, and violet – snow over a cemetery, any markers mere lumps across a vast mute field. Wash of beautiful colors overall does not mitigate the deadness of the scene, and of the silence, now that all movement has given in to rest once that last petal landed. A morbid sickly sweet incense lays heavy in the atmosphere, emissions from the grand pile. Birdsong asserts itself once again from open air, emerging through the silence, followed by hollow laughter of Heliogabalus, forced bored laughter as after a sick joke when even the joker finds its punch-line dull, unfunny, tedious.

Decadence, excess, the fascination of all the facts and myths pertaining to him – how much are lies and libels dated after his death and Damnatio memoriae, official erasure from history of disgraced persons (including the trashing of public records)? I do wish to affirm, from facts, conjectures, and calumnies alike, the mythic essence of the Heliogabalus “true tale” in all its transgressive glory.

For someone so supposedly vile and degenerate, quite a few interest groups claim him as their own, and not only hedonists, sex positive culturists, and gay-lesbian-bi communities, descendants of 19th century Decadents in appreciation of his flagrancy. Heliogabalus can be considered the first youth hero, of rock star proportions, flaunting his lust, luxury, and consumption of intoxicants; he was the first transgender person in the public eye (although hermaphrodites were prized in underground sex trafficking), cross-dressing on the dais of the throne, and consulting physicians on the feasibility of a sex change operation; and he was a feminist, and product of matriarchy, allowing women into the Senate – his mother and grandmother. Free Spirit can’t be pinned down.

Incisively, Artaud wrote about him as the Anarchist Crowned. But again, he was a priest of the sun, and I take him seriously in his fanatical identification with his sun God, and understand him in his primary goal of imposing, in a proto-monotheistic manner, Sol Invictus on the Roman Empire. Heliogabalus doesn’t exude wisdom as Akhnaton does; he was a madman, given absolute power at the age of 14, and did whatever he wanted to do. Yet he did it all for the sun. I delve into the nature of his ecstatic devotion in 8 Phases of Staring into the Sun, available in Eccolinguistics 2.1, a free pdf download. Be that as it may, Heliogabalus was divinely impolitic, lavish, and debauched, spread orgies and anarchy wherever he went, and had to be stopped.

A Gaze Free from Constraint

To cast upon the world a gaze free from constraint.

His head aloft, atilt, a pout plays around the lips, the scruff of a wispy downy beard tracing a sharp angle at the squared squat line of his jaw – a strong jaw, yet a small upturned mouth, wisps of hair on his upper lip, facial hair too thin to cover a pimple here and there. The curve at the corner of his mouth shows a hint of a smile, a pert boyish smile, stubborn, free, unbound by any promise: there isn’t anything mere humans can secure from the smile of Heliogabalus. His eyes are set. What does he want next, and what sure and tiresome thing does he have to do? What is he called upon to do? Yet it is all up to him – whatever the calling of his god. The sun is in his eyes. Swollen lower lids, shaded sunken half-circles, puffy, jaded; cut of the cheek sharpens the strong solid line of his nose, the shadow of his cheek against a fine shell of an ear. Golden tan, handsome. Set eyes. The face of today in all its youthful beauty, the rising man of this world’s tomorrow as if there were no tomorrow, the sun has always been in his eyes. A laurel wreath crowns his tight dark curls.

To cast upon the world a gaze free from constraint is to disintegrate the order of things in their apparent coherence, in their false stability.

A pulverizing of solid appearance into chaotic presence, the real violence of existence in the here and now.

Heliogabalus is Hypersigil

Magus Magnus is the author of The Re-echoes (Furniture Press 2012); Idylls for a Bare Stage (twentythreebooks 2011); Heraclitean Pride (Furniture Press 2010); and Verb Sap (Narrow House 2008).

Several of Magnus’ poems and an idyll have been anthologized in the 10th and 11th editions of Pearson Longman’s university-level English textbook, Literature.

His Poets Theater work has been presented in Washington D.C., Alexandria, Baltimore, New Orleans, and New York – highlights include Boog City Poetry, Music, and Theater Festival 7.0 and 7.5, two years in a row at Washington D.C.'s The Shakespeare Theatre Company’s “Happenings at the Harman” at Sidney Harman Hall, the Kennedy Center Page-to-Stage Festival, and a “Must-See,” 5-Star, “Best of the Fringe”-rated run for the 2013 Capital Fringe Festival.

He is curating the Boog Poet's Theater Festival to be held in New York in August 2014.